07.27.22Responding to Behavioral Breakdowns with Teaching Requires Preparation

In Reconnect my coauthors Denarius Frazier, Hilary Lewis and Darryl Williams, and I write about the importance of schools being prepared for behavioral breakdowns by being ready to teach in response to such behavior. Yes, consequences are often a necessary response. But they are far more effective if they are pared with teaching- with a school ensuring that a student understands how and why to respond differently. In fact sometimes the teaching can be rigorous enough—and provide students enough of a chance to show they are trying to do better—that consequences become unnecessary. But teaching in response to behavior is like any teaching in that it requires preparation and that, we note in the book, doesn’t always happen in schools.

Consider something as simple as writing a letter of apology to another student—let’s say after having deliberately thrown a basketball at them during a game of ‘knockout’ gone wrong.

What would you get if you asked a representative sample of students to write such a letter?

Some young people would write sincere letters using direct and accountable language. You’d notice sentences that began with the word I to describe what they’d done. (“I apologize for throwing the basketball at you.” Or “I threw a basketball at you today and I want to apologize for that.”)

They’d demonstrate their awareness of how their behavior made the other person feel. (“I know it must have hurt, and it was probably embarrassing too, with everyone watching.”)

Some might affirm their appreciation and respect for the other person. (“I want you to know that I think of you as my friend.”)

Some might express a desire to make amends. (“Maybe we could play knockout again at recess tomorrow.”)

Such a young person is far more likely to build successful and meaningful relationships as a result of the integrity, compassion, and empathy they are able to express. For this reason, we wish that every young person had the skill of writing a genuine apology.

But of course they don’t.

In addition to the heartfelt letter of greatest integrity, you would get, in your representative sample, letters from young people that were vague and merely “apologized” without apologizing for something. (“Jason, I am sorry about what happened on the playground. David.”)

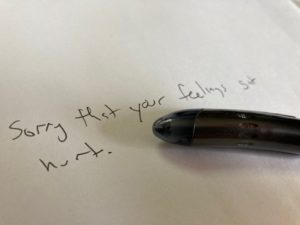

You would get letters that failed to take responsibility (“I’m sorry you got hit by the basketball”).

You would get letters that subtly (or not so subtly) blamed the recipient. (“Sometimes you act like you think you’re better than me, but that’s no excuse for throwing a basketball.”)

You would get letters that suggested the writer was unlikely to rebuild the relationship with the recipient going forward. (“Next time I will just try harder to ignore you.”)

If you are the one who deals with the young person who has thrown the basketball—and the thrower’s erstwhile friend has perhaps been sent to you as well—you have a lot of work in front of you if your goal is to teach the art of apology and the reflection and emotional self-regulation that come with it.

You will probably be engaged in the task of teaching two potentially emotional young people how to make a proper apology while you are doing other things. Perhaps there are other students in your office. Perhaps one of them is crying. Perhaps you have to go check on a student to make sure she’s doing okay today. Perhaps a parent has just shown up to ask for his daughter’s cell phone, which you confiscated yesterday.

Having a curriculum would mean having a lesson plan, or a series of lesson plans, about apologizing at the ready. You’d walk to your file cabinet and pull it out. It would be rigorous and challenging but also interesting.

Maybe it would start with a general reflection on apologies, something like this:

We all make mistakes, but how you respond to mistakes can make a huge difference in how others perceive you and the situation you were in together. Simply apologizing by saying “I’m sorry” is often a helpful first step in those moments.

When you apologize, you’re telling someone that you’re sorry for the hurt you caused, even if you didn’t do it on purpose. You are showing that you have the maturity to understand their point of view. Apologizing also often makes you feel better because you are clearly trying to put things right. That again is a sign of maturity.

When you say, “I’m sorry,” it helps people refocus their attention away from identifying who was to blame. Now you can be working together to make things better. It can help you maintain—and even strengthen—your rapport with others.

Stop and Jot: What are some of the benefits of apologizing when you’ve done something wrong?

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Then maybe it would ask students to look at some samples. Like this:

An effective apology should be honest, direct, and acknowledge that you did something that negatively impacted others. It should not cast blame on someone else or try to provide justification for your actions.

“I’m sorry about what I said to you.”

“I’m sorry I lost your book.”

“I shouldn’t have called you a name. I’m sorry.”

“I’m sorry I hurt your feelings.”

“I’m sorry I yelled at you.”

“I’m really sorry I hit you when I was mad. That was wrong. I won’t do it anymore.”

Stop and Jot: Why are these apologies effective? What are some things they share in common?

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Then perhaps it would ask them to reflect in writing on apologies they’ve experienced in their own lives, like this:

Answer the following questions in complete sentences.

- Describe a time when someone apologized to you. How did it make you feel? Why?

- When was the last time you apologized to someone else? Why did you apologize, and how did you feel afterward?

- When do you find it hardest to apologize to others? Using what you learned from the first reflection, what could you say to motivate yourself to apologize?

Then perhaps they’d be asked to apply their growing knowledge of apologies to situations they might face in the future. Like this:

Explain what you might do and say to apologize in these situations:

- You accidentally bump into a classmate in the hallway when you are not watching where you’re going. They drop all their things, which scatter in the crowded hallway. You mutter, “Oh, sorry,” but you don’t stop to help. You see him in class that afternoon.

- You promised your mom you would be home on time, but you did not make it home on time because you were talking with a friend and missed the first bus. She’d made dinner for you and it was cold. Now she is watching TV by herself on the couch.

- You were mad about something and were sulking in class. You didn’t participate at all and were looking out the window. Then you put your head down on your desk and said, “This is so boring.” You said it to a friend, but you know the teacher heard you. You’re in the hallway just before dismissal and see her standing outside her classroom talking to another teacher.

Then perhaps your student would write their letter of apology. Perhaps you’d provide them with a list of dos and don’ts as a helpful reminder. If they were struggling, you’d have a sample letter they could read and annotate.

As with any good lesson, you’d want to end with an assessment, an Exit Ticket of sorts that would allow you to see what someone understood differently now and maybe even how they might use it to respond differently to the situation they’d initially struggled with.

You could use some or all of these tools depending on the situation. Maybe your student who has thrown the basketball gets it immediately and is sincere and ready to write. He doesn’t need a lot of further analysis. But maybe he is just going through the motions and doesn’t really think he should apologize. In that case he’d then get different activities from the sequence of possible learning tasks you had available. Or maybe both participants in the incident have been sent to you and each owes the other an apology, but they are in difference states of readiness and reflection. In that case there would ideally be different tasks for each of the young men involved.

Ideally they’d work hard at the tasks—so hard, in fact, that further consequences wouldn’t really necessary. You’d simply make a copy to send home to their parents so they were aware of the situation and the work their child has done in self-reflection. Perhaps you’d ask the child to have the parents sign and return the letter. Then you’d put the student’s work in a file. You’d never see one of them in your office again, but the other one would be involved in a similar incident two weeks later. You begin then by taking out what the student wrote the first time around and asking them to reflect on how the two times are connected and why they were in your office again.

Really teaching about behavior requires content and preparation, this is to say. If we’re serious about responding to breakdowns with teaching, this is a gap we’ll have to close. Teaching in any setting won’t happen without meaningful things to teach, organized in a useful way. That means a curriculum, which in turn means planning and resources: perhaps a team of people, perhaps a few weeks of paid time during the summer to prepare lessons, perhaps the addition of a team member on staff whose job is to develop activities in response to incidents and then organize and file them so they can be reused and adapted.

It might seem like a lot, but with young people more and more likely to struggle at the skills required in challenging social situations, it is more important than ever to do the work in advance that allows us to teach in response to misbehavior.

As it happens we’ve written just such a curriculum. The books describes it more and there are details here as well.