09.01.15Reflections from Our First Workshop for Deans of Students

With our Deans of Students (and a few others). Love this group!

Two weeks ago week my colleagues Erica Woolway, Hilary Lewis, and I led our first Uncommon-wide workshop for Deans of Students. We got together with 60 or so amazing folks from across the organization who play a lead role in shaping behavior and culture in our schools. They inspired us and taught us, so I thought it would be useful, as the year starts off, to share some of our reflections.

The Differences between Behavior vs Culture

Behavior is what people do in a specific setting. Culture is the overall expectation around behavior: what we do more broadly and why we do it. It says, “This is who we are.” Culture focuses on what we want ‘doing it right’ to look like and why, not just making sure we don’t get it wrong. In the end it shapes behavior most of all.

A great school has to address behavior but its most important job is to build culture – to frame and normalize what we are doing in this building and why. Once it has been built, culture often shapes behavior invisibly and also provides tools for addressing it.

Consequence vs. Punishment

Schools have to react to negative behavior when it happens in order protect the school culture and each child’s opportunity to learn. This sometimes means sanctions. The key is to distinguish “consequence” from “punishment” and to always strive for the former. We spent a fair amount of time talking about the difference between consequence and punishment. First and foremost, the goal of a consequence is to teach. Our Deans observed that to do so, a consequence had to be logical and to the degree possible, predictable – you should know clearly what’s ok and what’s not beforehand and that it will work the same for everyone. That’s a form of fairness. Consequences should also start small enough so that students can learn from mistakes safely and at low stakes. This is critical in heading off more significant behaviors that lead to suspensions and the like. Consequences should also be both positive and negative, and they should be delivered in an Emotionally Constant teaching atmosphere and tone. Delivering them with anger only distracts students from thinking about their own behavior by causing them to also think about why someone is yelling at them. But most of all, consequences have to involve teaching and explanation: This is what we are all striving for. This is why. This is how what you did was different, and this is what you can do to put it right and learn from it. Deans, in other words, must first and foremost be teachers.

Public Deaning vs. Private Deaning

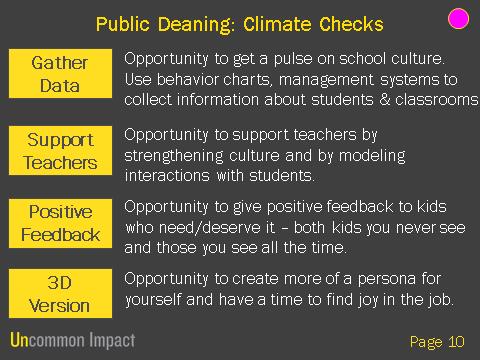

We also talked a lot about “public deaning.” How effective deans get out of their offices and into public spaces, interacting constantly with students and teachers, building positive relationships and investing in prevention. Here’s one of our slides that describes some of the goals of Public Deaning and why it’s so important.

As for Private Deaning—the job of meeting with students to discuss their behavior when it has been negative in some way—a couple of key points came out, especially regarding what happens AFTER a consequence. First there was teaching, calm caring teaching, and then the importance of “Building Them Up” and “Locking It In.”

Building Them Up: After a student has received a consequence is often the most important time to remind them that you believe in him or her. The message is: “you made a mistake; in life there are sometimes consequences; but I care about you and want to help you do your best… and I know you are going to succeed.”

Locking It In: This is where you make sure a child understands what happened and how to approach a situation differently next time. It’s a re-cap of the learning, in the student’s own words. If students can’t do this, the process may not have focused enough on teaching.

“Back to Class”: Our Deans also shared a lot of brilliant things they do when they bring a child back to class. Instead of just sending them in, for example, some Deans go and sit with the child for a few minutes to make sure they transition effectively. When they leave they say, “OK, I can see you’ve got this,” and sometimes, “I’m going to step away, and I’ll check back in a bit.” This is an easy way to remind a child that they have re-entered successfully and (if you add the second phrase) to remind them to continue meeting that level of behavior. It’s also useful because if a teacher feels like a child has been disrespectful, he or she can see that the Dean has been attentive but also accountable—in the best sense of the word—to a colleague for letting the student back into the classroom without bearing a grudge.

This is an important part of the work of Deans. Students make mistakes and there are sometimes consequences. But it’s important that every student start over with a clean slate after the consequence. That’s one of its primary purposes. You’ve made amends and once you’ve done that you are supposed to get a fresh start.

A last thought. Julie Jackson, our Chief School Officer at Uncommon stopped for part of the workshop. She’s a master of dealing with challenging kids.

Here’s a quick story by way of example: Several years ago, Julie described to me how she’d come up with a variation on one very common consequence.

“I called my scholar at home to speak to his mother after he’d had a bad day and he answered, so I said, “This is Ms. Jackson, may I speak to your mother?” and he said, “She’s not home. It’s just me and my sister.” I could tell he wasn’t lying, and it was pretty late. So then I understood a lot, and I said, “OK, well then you are a young man, and you and I will talk. And I said everything to him that I was going to say to his mom: This is what you did today, this is why it’s not acceptable in school, and I know you are capable of much, much better so this is what I want to see from you tomorrow. Do you understand? I am going to see that tomorrow, correct?” And the next day he acted just the way we’d spoken about.” Julie had invented, spur of the moment, the student phone call in lieu of the parent phone call.

At the workshop, Julie shared this thought about a very technical detail: the use of the What to Do technique in the Dean’s office. Many of our Deans, we noticed, ask students to start by doing something very small and very specific in a calm tone of voice when they enter. “Sit down in this chair please.” “Track me so we can discuss.” Asking for a very small, clear specific “in-task” not only establishes that a student is ready to listen and talk, but as Julie pointed out, it allows you to instantly recognize their efforts to be positive and do as they are asked and to reinforce this right away. The first thing you say is “Sit down in this chair please.” “Track me so we can discuss,” so that the second can be, “Thank you. I can see we are going to get to the bottom of this quickly.” Or “Thank you I can see you making an effort to do the right things now.” This, she observed, provides a way in, especially with an emotional student or one who feels misunderstood. It allows students who want to turn it around to show it in a very small way and for you to acknowledge it very simply as a first step. The result is often a win for everybody.