03.02.19Learning to Emphasize Background Knowledge in My Own Reading

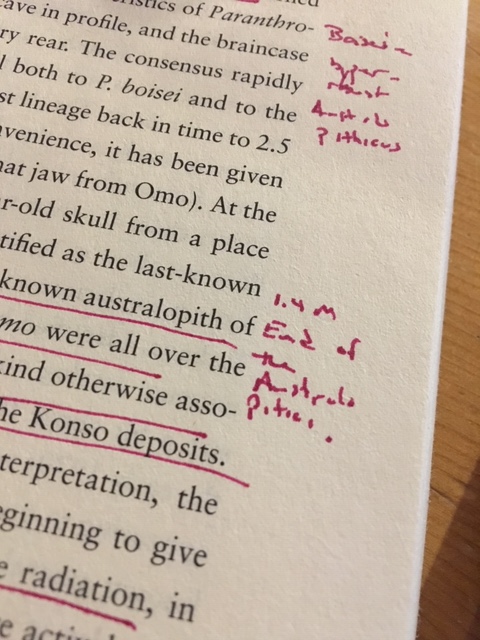

A knowledge-based margin note: M y scrawl says, “1.4M {years ago]. End of the Australopthicus.” I never would have written that kind of margin note before I started understanding the importance of encoding knowledge in long-term memory.

I’ve been thinking a lot about reading lately, and not just students’–my own as well.

This week EducationNext ran a review I wrote of Maryanne Wolf’s Reader Come Home, it was a review about an immensely important book that was also one of the most soul-searching things I’ve written in some time. Here’s an excerpt that captures the gist of it:

On the digital screen we read fleetingly, flittingly. Our brains have what scientists call “novelty bias.” … We are repeatedly distracted by whatever pops up, rewarded for each distraction with a tiny surge of dopamine. This attraction to “the new” crowds out reflection, creative association, critical analysis, empathy—the keys to what Wolf calls the “deep reading process.” We read in a constant state of partial attention…

We made ourselves modern via a collective rewiring [of our brains] when writing and later print emerged and spread across vast strata of society not so long ago. … Reading taught us to sustain and logically develop ideas, to enter the minds and perspectives of others through their words. As societies, we became less impulsive, violent, and irrational.

“The long developmental process of learning to read deeply and well . . . rewired the brain, which transformed the nature of human thought,” Wolf writes.

Now there is a new transformation taking place. Skittish, distracted readers rewire differently from thoughtful and meditative ones, and so they—and the collective “we”—come to think differently, to develop different architecture for thinking. Through disuse, we are losing what Wolf calls “cognitive patience,” and thus the ability to immerse ourselves fully in books.

But in addition to struggling with my own diminished focus during reading, I am struggling with other flaws in my reading.

I am struck for example that I remember so little of so many of the books I have read. I have read several books each on the life of Winston Churchill, a few on technology in Medieval society, and the voyages of James Cook–I remember loving the books and finding them valuable. They sit now in a place of pride on my bookshelf. But ask me even the most basic questions about them and I would struggle to answer.

I find this distressing–have I really read a book if I don’t remember it? What is the difference between reading a book and mastering it (a phrase I saw used by a 19th century diarist in describing why he was reading a book for the third time)? These questions seem important as I understand more about the critical role of long-term memory in higher-order thinking. In the midst of trying to write a curriculum that asks students more knowledge-based questions, I now find I need to adjust my own reading to prioritize knowledge more.

I’ve been doing two things. First I’ve gone back to keeping a commonplace book, a journal I use to transcribe passages I want to remember from books I am reading, sometimes with brief reflections and commentary, sometimes without. Writing helps me to remember. But each time I enter new passages I also try to re-read entries on previous books, so I am constantly reviewing the key ideas from my reading year.

I bought one that was super slim so that I could easily put it in my bag and have it with me anywhere… I wanted to make it easy to use, to reduce transaction cost. I also make sure to keep it separate from my other notebooks… thus the distinctive color.

Thin and easy to slip into my work bag–reducing transaction cost.

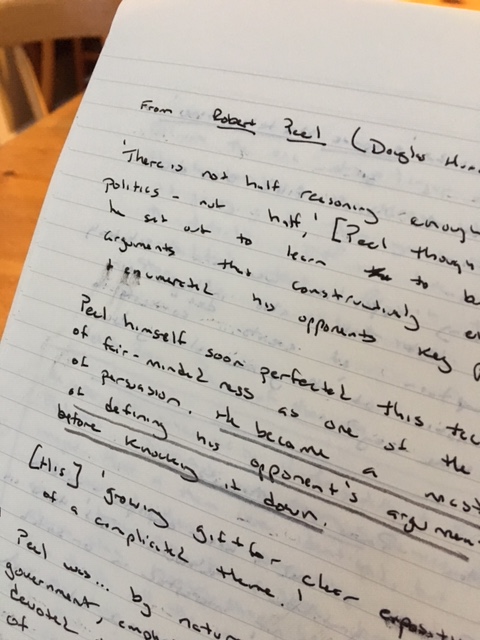

Read a Biography of Robert Peel… a few memorable passages written here and hopefully into memory

The other thing I’ve been doing is doing retrieval practice during my reading. So, for example, I am reading Ian Tattersall’s, Masters of the Planet: The Search for Our Human Origins–it’s basically an analysis of what we know about the hominid forebears of mankind.

I want to remember more than just the gist. I want knowledge I can use not just a lively read. So I am trying to not just make margin notes with my personal reflections as I read–a deeply ingrained habit–but also to add ‘factual margin notes’ in which I write down points of knowledge I want to remember:

- Miocene, about 25M years ago, golden age of apes.

- Pliocene, begins 5M years ago, earliest hominids, climatically disruptive

In another cases I’ve made lists of the major hominid groups in chronological order so I could keep them straight and remember them:

- homo habilis–2M years ago

- homo ergaster–1.8M years ago

- homo erectus–1M years ago

- homo sapiens

Again these are much more mundane and fact-based than the notes I have made heretofore in my reading life, but I realize that, as we do with our students, I have overlooked the importance of knowledge, encoded in long-term memory, for my own learning and enjoyment. If I can put the facts in my long term memory I can use them for a dozen unforeseen insights, rather than just tracking the insight I have now as it’s fresh in my mind. I still do that, but disciplining myself to get down facts I would have previously overlooked has been really fun and makes me feel like I know that books I’m reading far better than I previously did.

But then again I should probably wait a few years before I decide I’ve made progress.

[UPDATE 3.3.19: Reader Mark Anderson of New York suggests supplementing this idea with ANKI, an app that allows you make bespoke, online flashcards for easy review of whatever you’re learning. I’m going to check it out.]