04.14.20Zack Ohlin on Developing His Athletes’ Perception with Virtual Workbooks

Last week I posted an article about using quarantine as an opportunity to improve young athlete’s capacity to learn by watching. My post described how you could set a singular and focused observation task, but it seems that Zack Ohlin was a couple of steps ahead of me.

Zack’s a tennis coach in Vancouver, BC with whom I correspond about coaching and develop athletes.

“When this all hit the fan a few weeks back,” Zack wrote, “I designed an at-home tactical workbook that covers patterns, tactics/strategy, tactical anticipation, and charting. Each section has homework that requires players to watch match video, either of themselves or others, and observe certain things. I’ve been rolling it out for the last 2 weeks, giving feedback on the homework via email and following up via Zoom every 3-4 days or so.”

He shared a copy of his At-Home Tactical Workbook (you can check it our for yourself here: https://www.zackohlin.com/resources) and I was both impressed and full of questions. Zack agreed to answer them as part of a blog post so other coaches could benefit from his work.

How did you get the idea to give your athletes this kind of ‘at home tactical work’?

The impetus was twofold: I wanted to make sure that we were staying in touch with our athletes and showing that we cared about them, and I felt that this was an opportunity for our athletes to surpass others who might not be as motivated. From there, I had to look at what could and couldn’t be improved from home. I’m not a big believer in shadow swings and technical development that doesn’t involve a ball and a court, so that was quickly ruled out. Our Director of Strength & Conditioning was already working with the players on their physical fitness, so that left me with the mental and the tactical.

For one of your assignments you asked players to watch a match and look for things like how players got to the net and what kind of passing shots they used and email you their responses. Before you sent them off to do this assignment you gave them a primer on relevant knowledge and vocabulary: There are four main ways to pass. Here they are. Now see if you can spot them. Why did you decide to start with the background knowledge, rather than just asking athletes to derive the four ways passing shots worked?

In tennis, you are making decisions about a large number of factors based on a similar number of factors. So, it’s very complex. You must perceive ball height, speed, spin, depth, and direction; your opponent’s technique and court position; and your own position. In terms of decision-making, I believed that the greatest learning would come if I provided a framework (power, precision, at the feet, lob). I was worried that they would end up observing factors that were less useful in this instance (eg. stroke, or stance). I wanted to help them focus quickly on what was important. The answers I got were great and showed a lot of effort. I was surprised by their confusion over what was an approach versus an “attack and follow”, but it taught me that they didn’t know what to look at (the feet) or how to be able to determine when a player was making the decision to come to the net.

Another assignment was to watch a match between Djokovic and Nadal and try to observe something tactical each player was doing. That’s a tough assignment! What was your purpose in giving it and what kind of responses did you get?

You’re not wrong! In fact, before sending out the homework, I changed it, and had the players watch college matches instead (still a very high level of tennis!). While it might seem like watching a high-level match and picking out tactics could be overwhelming, what I was asking for was actually relatively simple: to notice any patterns or tendencies that were unusual. I gave them a framework that could help their observation: stroke, court position, game situation, phase of play, or score. That way, they could pick out anything a player did in one of those categories that happened more than a few times. For example, if a player chose to attack their backhand down the line more often than crosscourt, or if a player chose to “wrong-foot” a player (hit behind them rather than to the open court) more than usual. My intention was to help the players learn to identify trends (things that are happening repeatedly during a match) because that ability is the foundation of what we call “tactical anticipation” – the ability to anticipate what someone is going to do based purely on your knowledge of their tendencies. The responses were encouraging and revealed a lot about the players’ understanding of what is common and uncommon. Almost everyone was able to identify two or three tendencies – some were more useful than others (because they were more unusual), and a few were really interesting!

It seems like there were two kinds of assignments you were giving: technical—here are four ways to execute a passing shot—and tactical—here’s how to read what your opponent is up to and change your play accordingly. Are there any other types of assignments you’ve given? For example do you ever ask about technique (e.g. what do you notice about Serena’s footwork in this sequence?)

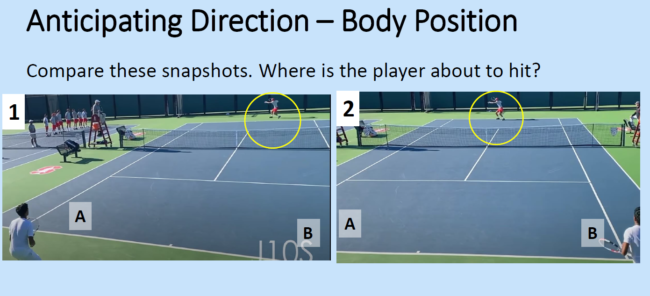

It’s always interesting to delve into other sports and look not only at differences in methodology but also in language, because in tennis we would call both of those tactical. For me, anything that involves decision-making is tactical, and that was the purpose of teaching them the four ways to pass – to plant the seed for them to start thinking about which passing shots they should use, and when. At no point did we talk about anything “technical” (footwork, bodywork, or racketwork). As I mentioned earlier, I’m not a big believer in technical development that doesn’t involve a ball and a court – tennis is so complex and open that it is very hard to develop technique well without that “real” feedback. That being said, I’ve also just developed a workbook that that deals with what we call “technical anticipation” – the ability to anticipate what someone is going to do based purely on elements of their technique. This might be of particular interest to you and other soccer coaches, as we talk about reading grip, racket angle, racket path, body orientation, impact point, and other factors.

You ask players to study both the matches of elite professionals and their own matches. Were both tasks equally useful to players? Were players equally perceptive in looking at both?

That was important to me – to provide a wide range of matches to watch. They watched professional and college matches (men and women), their own matches, and some international level junior matches. Interestingly, their observations were better when watching the professional matches. I’m going to tentatively ascribe that to two factors. First, the majority of our players watch more professional tennis than junior tennis. When they’re at a tournament, if they are off court, they are stretching, warming up, resting, eating, etc. And when they are on court, they are certainly “seeing” things, but it’s not from the same perspective, and I wouldn’t call it “watching.” Second, when we are looking to identify tactics, I think it may be easier when watching higher level tennis because there is a higher chance that the player will be successful. At lower levels, players may be intending to do something but not always executing, and this can be hard to pick up on video.