08.08.22Respecting Young People’s Ability to Decide About Using Phones in School: A Historical Perspective

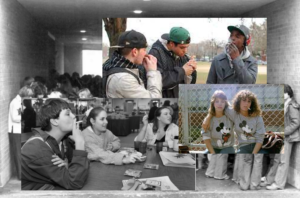

Acceptance of and respect for young people’s autonomy, circa 1985

Here’s an excerpt from the TLAC Team’s forthcoming book, Reconnect: Building School Culture for Meaning, Purpose, and Belonging by coauthors Doug Lemov, Hilary Lewis, Darryl Williams and Denarius Frazier. One of the themes of the book is that in a time of difficulty schools will have to choose between building the best possible environment for achievement and belonging and their willingness to tolerate the presence of cellphones during the day. Doug had an article on the topic in Education Next this past week if you want to read more about why. At the beginning of Chapter Two of the book, we make the case via analogy:

Doug attended high school in the 1980s. In addition to this making him the “senior” member of the team, as we tactfully put it, this gives him some stories to tell from a different era. Here’s one that his own kids find jaw-dropping:

He and his classmates were allowed to smoke in high school.

Actually, smoking was more than allowed. It was more or less enabled. There was a student smoking area with ashcans. It was marked on maps of the school. Smoking was legal, after all, and one common argument was that it wasn’t really the school’s place to restrict it. People also argued that teenagers would smoke anyway. Why not give them one place to do it so there weren’t butts everywhere on campus? Why not make it convenient so they weren’t also late to class?

It sounds crazy now, but at the time the administration argued that high school students were adults entering a world in which, it was noted, there would be tobacco. They would have to learn to make decisions about tobacco. The administration’s goal was to educate students to think for themselves.

They didn’t really do much educating in practice though. There were posters about making smart choices and an occasional cautionary video, but we all know how well those work. Plus, if teachers were supposed to “talk to students about tobacco,” they didn’t really know

how. Occasionally one might remind students that they shouldn’t smoke, but they were there to teach math, history, and art. Plus many of them were smokers themselves. A few occasionally allowed students to bum cigarettes from them. From the students’ point of view, this earned them status. Students liked to be “treated like adults.”

All in all, the argument was that it was clearly better not to come on too strong with the restrictions. The smoking area reflected school’s acceptance of and respect for young people’s autonomy. At least that was how they explained it. It’s possible they just didn’t want to make rules about smoking because they didn’t want the unpleasant job of doing something teenagers would have resented. Teenagers are good at making it difficult emotionally to do things they resent. It’s also possible that they hadn’t thought that a rule could be beneficial even if some people broke it.

All the while, everyone knew the truth about cigarettes. The data on the long-term health effects was readily available; it had been for years.

The upshot was that a lot more people became smokers. Needless to say, they paid a high price for that decision. It was their decision, of course. They’d probably be the first to tell you that. But it does seem odd, looking back, that the school made it so easy to access a demonstrably harmful product that was designed to addict young people. And the 16-and 17-year-olds whom everyone was so eager to christen “adults” were of course not adults. They were teenagers. Their prefrontal cortex would not fully develop for nearly ten years (around age 25). This made them especially susceptible to addiction because they were at the point in their lives when they were most influenced by their peers and most likely to make decisions that ignored danger and long-term consequences.

But it does seem odd, looking back, that the school made it so easy to access a demonstrably harmful product that was designed to addict young people. And the 16-and 17-year-olds whom everyone was so eager to christen “adults” were of course not adults. They were teenagers. Their prefrontal cortex would not fully develop for nearly ten years (around age 25).

Of course, the teens wanted to be seen as adults. They argued this especially vociferously when it might result in additional freedoms, but the educators really should have been able to see the difference.

As you might have guessed, this story isn’t really about smoking in schools in a bygone era but is intended to make a point about cell phones and social media in schools today—specifically tolerance of something so damaging and addictive to young people. We also hope to point out that the arguments about why schools can’t or shouldn’t restrict cell phones are similar to the ones made about cigarettes at Doug’s school. Educators argue that schools shouldn’t restrict cell phones because it keeps young people from learning to manage their phones for themselves, because rules don’t work, because it fails to treat teenagers like adults.

And, sadly, as there was with smoking, there is damning data on the danger of the product and of teens’ particular vulnerability to it.

The analogy to smoking is flawed of course. People interact with cell phones and social media differently than they do with cigarettes. Cell phones are more harmful in some ways and less harmful in others. They are more directly disruptive to the cognitive processes of learning, for example, and are far more ubiquitous: absolutely everyone has one and, unlike cigarettes, left to their own devices students would and do use them in the classroom. A recent survey in the UK by Teacher Tapp, a daily survey app for teachers designed to gauge the experience and opinions of the field more accurately, asked teachers whether at least one pupil had taken their phone out during class without permission during the previous day alone. Of almost 4500 respondents, one-third said yes. Some teachers reported it happened

to them multiple times every day.

On the other hand cell phones also have clear benefits. We’ll merely acknowledge them here without trying to describe the obvious in terms of their capacity to provide access to information and facilitate communication in a hundred ways. And it’s worth noting that while we hesitate to use the word “benefits,” there were also reasons why so many people smoked. The biggest one, probably, is relevant to the themes of this book: the sense of belonging and camaraderie that came from standing in your denim jacket sharing a cigarette on a chilly morning. It made you part of a community—one for which you were willing to make certain sacrifices to belong.

To state the obvious, then, cell phones are not cigarettes, and the appropriate response should reflect the differences. But it should also reflect the fact that in our schools we tolerate a highly destructive product specifically designed to addict young people, and distract them from learning. Permitting cell phone use (and saying we are treating young people like adults when we enable their addiction) is not a viable policy in an institution committed to learning and building well-being.