04.03.17Bloom’s Taxonomy—That Pyramid is a Problem

It’s hard to find a teacher who doesn’t make reference to Bloom’s Taxonomy. It’s part of the language of teaching. For those who aren’t familiar with it here’s some background from Vanderbilt’s Center for Teaching:

In 1956, Benjamin Bloom … published a framework for categorizing educational goals: Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. Familiarly known as Bloom’s Taxonomy, this framework has been applied by generations of K-12 teachers and college instructors in their teaching.

The framework elaborated by Bloom and his collaborators consisted of six major categories: Knowledge, Comprehension, Application, Analysis, Synthesis, and Evaluation. The categories after Knowledge were presented as “skills and abilities,” with the understanding that knowledge was the necessary precondition for putting these skills and abilities into practice.

Bloom’s Taxonomy is often represented as a pyramid with the understanding—intended or accidental—that teachers should try to get to the top. That’s the nature of pyramids, I guess.

A couple of useful notes though. 1) Bloom’s is a ‘framework.’ This is to say it an idea—one that’s compelling in many ways perhaps but not based on data or cognitive science, say. In fact it was developed pretty much before there was such a thing as cognitive science. So it’s almost assuredly got some value to it and it’s almost assuredly gotten some things wrong. 2) I was surprised, happy and concerned (all at once) to read the italicized phrase: with the understanding that knowledge was the necessary precondition for putting these skills and abilities into practice.

Ironically this is exactly the opposite of what people interpret Bloom’s to be saying. Generally when teachers talk about “Bloom’s taxonomy,” they talk with disdain about “lower level” questions. They believe, perhaps because of the pyramid image which puts knowledge at the bottom, that knowledge-based questions, especially via recall and retrieval practice, are the least productive thing they could be doing in class. No one wants to be the rube at the bottom of the pyramid.

But this, interestingly is not what Bloom’s argued—at least according to Vanderbilt’s description. Saying knowledge questions are low value and that knowledge is the necessary precondition for deep thinking are very different things. More importantly believing that knowledge questions—even mere recall of facts—are low value doesn’t jibe with the overwhelming consensus of cognitive science, summarized here by Daniel Willingham, who writes,

Data from the last thirty years lead to a conclusion that is not scientifically challengeable: thinking well requires knowing facts, and that’s true not simply because you need something to think about. The very processes that teachers care about most — critical thinking processes such as reasoning and problem solving — are intimately intertwined with factual knowledge that is in long-term memory (not just found in the environment)

In other words there are two parts to the equation. You not only have to teach a lot of facts to allow students to think deeply but you have to reinforce knowledge enough to install it in long-term memory or you can’t do any of the activities at the top of the pyramid. Or more precisely you can do them but they are going to be all but worthless. Knowledge reinforced by recall and retrieval practice, is the precondition.

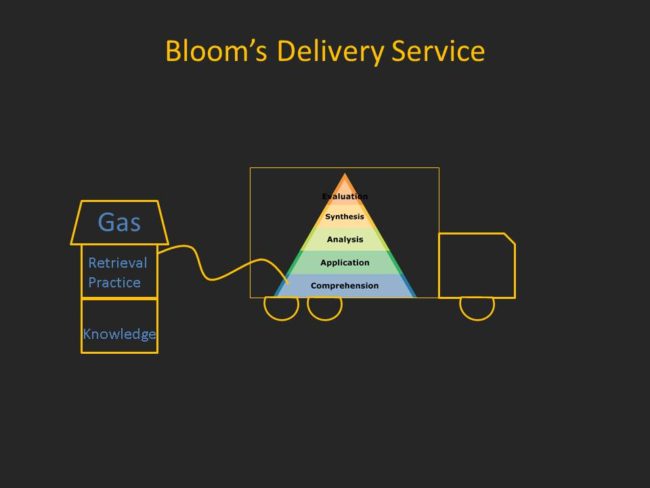

Bloom’s Delivery Service

In the spirit of the FDA which recently revised its omnipresent food pyramid to address misconceptions caused by the diagram created to represent it, I’m going to propose a revision to the Bloom ‘pyramid’ so the graphic is far more representative. I’m calling it Bloom’s Delivery Service. In it, knowledge is not at the bottom of a pyramid but is the fuel that allows the engine of thinking to run. If I had more time for graphic design, I might even turn the pyramid on its side. You probably want to do quite a bit of analysis and synthesis but only if you’ve got comprehension solidly in the bag. In other words you kind of need all of the pieces.

I like this, but the other way to think about this is that the lowest layer of the pyramid is the foundation—the part without which everything built on top collapses…

+1 to Dylan’s comment, above. In my book and in work I’ve done with educators on this very topic, I suggest rebranding the ‘lower order’ to ‘essential order’ for that very reason. No question, the poor instructional choices we’ve made (and, obviously, all the kids’ potentials we’ve left to rot) as a result of this misreading/misapplication are astounding.

Thanks, Eric. Love your re-branding.

Thanks, Dylan. Agree with your take–and love your visualization of it, by the way–but don’t think the ‘average teacher” sees it this way. I wrote this post last week after leading a workshop and hearing three comments in a row dismissing “lower order, fact type questions.” 🙁

I like this – a lot. It answers a lot of questions for me. For instance, when teaching Science or Social Studies in the early years, our suggested curricular lesson plans ask us to activate prior knowledge about a topic, when in fact most students don’t have much of the prerequiste knowledge. I have to do front-loading before I can even get them to understand the topic. It seems to me that the suggested lesson development is the wrong way around and, in order to promote real learning, I have to find ways to teach those very important facts first, before attempting to get the students to apply anything to their own lives via critical thinking.

Thanks, Kathy. I agree. I also think there’s a synergy there. When students go back and forth between learning things and wrestling with applying them and then going back to learn more and then applying they come to see the connection between knowledge and wisdom. At least I think. Best, Doug

I think it still come down to what knowledge and facts are important enough to have enduring value?

Surely, all facts are the not equal

What if the pyramid was more like a Jenga stack? You wouldn’t want to remove a bunch of pieces from the bottom right away, because then the whole thing would fall over. You would have no chance to reach a tall height. You can’t get to higher order thinking without first having Knowledge as a prerequisite.

These interesting points have made me wonder a couple of things. Here they are in order of wondering:

1) All the higher order skills seem to act to reinforce the knowledge or the facts. Perhaps a circular model would be suitable.

2) Doesn’t it all depend on what we mean by knowledge and how knowing occurs? If I remember rightly and can be forgiven for putting it so simply and perhaps applying it skewiffily, McGilchrist suggests a global>local>global model, which I suppose could be translated to HOTS>LOTS>HOTS.

3) The HOTS are transferable – if you can analyse one thing, you can analyse something else . As skills, they don’t rely on knowledge of specific facts: the analysis can reveal facts or lead to the need for facts. I don’t know what model would represent that – it seems like there are two different sets of things going on: knowing facts and using your brain.

I appreciate have got myself in a tangle here, I haven’t read Bloom’s original work and I was up late last night. So any thoughts you may have would be much appreciated!

” The HOTS are transferable – if you can analyse one thing, you can analyse something else . As skills, they don’t rely on knowledge of specific facts”

Respectfully, I completely and utterly disagree with all of the above. Analysis, problem solving, critical thinking are not generic skills which exist in isolation: they are completely and utterly dependent on the field to which these skills are to be applied, and hence is totally reliant on a good sound knowledge of that field.

Analysing a Maths problem is nothing like analysing a Historical text which is nothing like analysing a Poem.

Speaking as someone with a PhD in Maths in Geometry I can say with total confidence that I couldn’t come close to solving a similar problem in say Probability (I could of course solve an undegraduate level problem in Probability, but that is because I studied Probability to an undergraduate level).

This is a crucial point, and it cannot be reiterated enough, I also keep encountering the dismissal of the lower levels.

My approach to explaining it visually is by using a different pyramid model, that shows what happens when we try to build higher-order levels without the basis (still exploring people’s reactions to it).

https://sites.google.com/view/efratfurst/pyramids

and I now added this post as a reference.

This is a very interesting discussion thread! I really appreciate the perspectives shared. The problem may be more with perspective and perception more than anything else. In the revered and longstanding pyramid representation, knowledge is at the bottom. This doesn’t have to be the disdained component of the hierarchy. I mean, how many of us feel that the foundations on which our homes and other buildings sit are useless? Furthermore, Anderson, Krathwohl, and other former Bloom’s doctoral students (2001) offer us deeper insight into the framework and now characterize learning as two- dimensional. The 2001 text is worth a read.

I’d like to put forward an alternative perspective where we no longer discuss ‘higher level thinking’ at all, but instead, talk about deep thinking and how it is attained. Levels of thinking (I prefer to call these types of thinking) are inextricably linked. Based on what we know about how the brain processes information, I’d like to see teachers and students consider the cyclical, adaptive nature of thinking. New information enters the brain via the sensory register and if it is attended to, it moves into the working memory for conscious processing. This new information is processed (analysed, evaluated and synthesised) in relation to schema in long term memory. It is this processing that results in the development of a new understanding. With this new understanding in place, the learner takes in further information; it is analysed, evaluated and synthesised, this time at a deeper level, and understanding is developed at a deeper level. Superficial knowledge and understanding deepens over time through cyclical processing. When a learner’s understanding is superficial, his ability to analyse, evaluate and synthesise is superficial (but critical to the development process). As the learner’s knowledge and understanding deepens so too does his ability to process or analyse, evaluate and synthesise. Analysis, evaluation and synthesis are required for understanding to develop. They do not follow understanding.

If this resonates with you, you may be interested in reading:

http://www.laneclark.ca/thinking-about-thinking/

http://www.laneclark.ca/what-if-thinking-is-cyclical-and-adaptive/

I have tried a SWOT analysis on Bloom’s Taxonomy.

https://purnima-valiathan.com/blooms-taxonomy-an-open-letter-to-benjamin-bloom/

Thanks for sharing this. Interesting read!

Comment from someone in higher education. My experience is that no-one I know who is actually teaching a subject, as opposed to being an educationalist, believes in Bloom’s Taxonomy. People come and tell us how great it is, and how we must write documents in it. We smile and nod and do so in the hope that they will go away and let us do our jobs.

It may be more use in K-12 school education of course.

Fair point. It’s so commonly held and ascribed to in the K-12 world that it’s hard to ignore. And it’s a theory that people generally use because they want to do the right things. So it’s importnat to help them use it for good rather than ill. But I don’t disagree with anything you said. In the end it’s a theory… and it can become a distraction….