01.22.23A Slightly Annotated Willingham on Science of Reading

UVA cognitive psychologist Daniel Willingham and Barbara Davidson of Knowledge Matters were on the Melissa and Lori Love Literacy podcast a few days ago. About ten minutes into the discussion, Willingham gave a fantastic explanation of the role of background knowledge in reading comprehension. I transcribed the key sections below with a few notes of my own [in italics] added in for amplification or emphasis.

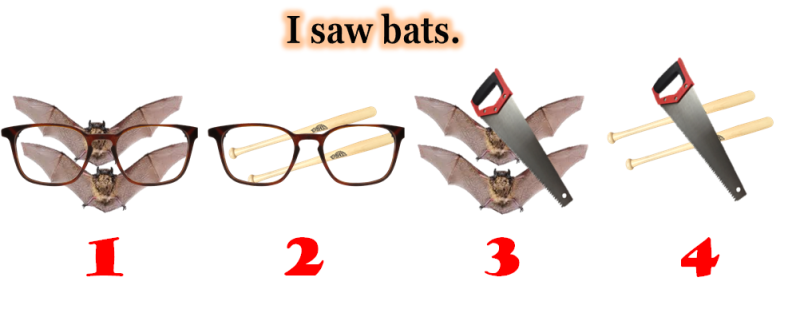

Willingham: The key feature of not just written but oral language is that language is sometimes [you might even say ‘always’ or ‘inherently’ I’d argue] ambiguous. And frequently a good deal of information that the speaker or writer intends their audience to understand is actually omitted. And it is in resolving his ambiguity and replacing that missing information that reader knowledge is so important. [The term for resolving this inherent ambiguity is: disambiguation. And (epiphany here): we are always disambiguating the language we read and hear]

Willingham provides an example sentence made up on the spur of the moment: “Lori tore up Melissa’s art work. She ran to tell the teacher.” He goes on:

The second sentence is ambiguous. “She” could refer to Lori or Melissa. But clearly if you’re an experienced reader [or listener] you’re not going to see that as ambiguous. You’re going to understand that you run and tell the teacher not when you are the perpetrator of a crime but when you are the victim of a crime. So that’s how “she” gets disambiguated. That obviously depends on some knowledge of the world. But pretty much everyone listening has that knowledge so it [the disambiguation] is simple.

This is an example of grammatical ambiguity at the level of the individual sentence. Once you get to making inferences across sentences … knowledge is even more important.

Willingham provides an example sentence from his book: “Tricia spilled her coffee. Dan jumped up to get a rag.”

If all you understood was the literal meaning of the two sentences you probably would not have understood everything the author intended. The author intended for you to draw a causal connection between the sentences: Dan jumped up because Tricia spilled her coffee.

But…you need to have the right knowledge to build that causal bridge. You have to know that when you spill coffee it makes a mess. You have to know that rags can clean up a mess. And so forth.

All of this is just stuff that the writer left out. The reason authors write this way [and speakers speak this way] is that if you actually gave all that information, the text would be impossibly long and boring. [Epiphany: the gaps the author leaves and that cause challenge for readers with knowledge gaps are a feature not a bug of language]. “Tricia spilled coffee. Some of it went on the rug. She did not want coffee on her rug. The rug was expensive.”

Willingham notes this would be absurd.

Knowing your audience means tuning what you say and write to provide as much information as your audience needs, but not more. [Every author is making assumptions about optimal knowledge of readers required to a) disambiguate and then b) understand at a substantive level what he/she is saying.]

Willingham next discusses the Recht and Leslie “baseball study” and then goes on to describe a second study by Ann Cunningham and Keith Stanovich:

“Who is it that does well on reading comprehension tests? Cunningham and Stanovich asked that questions in a series of studies. [The hypothesis was that “the kids who know at least a little something about lots and lots of topics would test well].

Most things you read that are for a general reader, the author is not going to assume you know a whole lot. They’re not going to assume you know that Picasso was a cubist, but the are going to assume you know that he was an artist and a painter. So you need to be a million miles wide but only a couple of inches deep to be a good reader [that is, to succeed on reading comprehension tests; though to be fair that only applies if you are a fluent reader with flawless decoding and if you also have knowledge of vocabulary]. So they tested that–a test of broad knowledge –who was Picasso etc?–this was with college students–and then they administered a general reading comprehension test. And they expected a strong correlation and that’s exactly what they observed.”

I thought that was a really elegant and clear description of the role knowledge plays in comprehension of text. We (or I) often focus more on the role of background knowledge in bigger inferences in the text–the ones an author might deliberately place allow to exist in a text. But really its critical role is in the constant and perpetual process of disambiguation.