02.26.18This Week: The Story of a Turnaround

The same kids–one year later

School turnaround poses some of the most critical questions in education reform:

- Is it possible to take schools that are failing and, with the same kids, achieve better results?

- What are the keys to succeeding? Are the lessons and practices that yield results scale-able?

The answers to these questions matter deeply in light of the number of kids who attend schools that do not prepare them academically. Since these schools overwhelmingly serve poor and minority families those answers are central to maintaining meritocracy and fairness in our society.

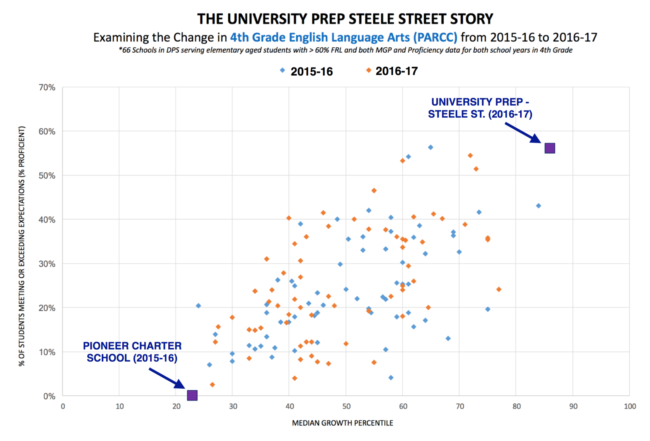

Over the next few days, I’ll be sharing a series of blog posts written by David Singer and his staff at University Prep – Steele Street. They took over a struggling school in Denver in 2016 and achieved dramatic results (see above).

David, the founder and Executive Director of University Prep, will be the first to tell you there’s a long way to go before the race is run.

But there’s a lot to learn from the early results and the lessons he and his team describe in these blog posts, so I hope you’ll tune in to read.

I should note that one of the things that makes University Prep’s Steele Street turnaround so interesting is that it wasn’t a district-to-charter turn-around. It was a charter-to-charter turn around.

In other words it isolates the critical nature of the decisions David and his team made and the nature of their execution, separate from the flexibility and autonomy granted to charters. It should remind us that flexibility and autonomy are no guarantee- they can allow well-meaning people to make sub-optimal decisions as much as optimal ones.

But, importantly, the University Prep – Steele Street turnaround was done with the same kids and many of the same adults who’d been in the building before. So it should also remind us, most of all, of the potential in every group of children- a potential it is our obligation to develop fully.

A historical note: Somehow a group of cynics has co-opted the term ‘no excuses’ to make it synonymous with ‘zero tolerance’ discipline policies- which few of the schools they use the term to describe actually adhere to.

Regardless this is not what that phrase meant to the people who coined it. The term described an ethos they thought was critical- one wherein the adults would not accept excuses from themselves or any other adult when students did not succeed. The term had everything to do with personal responsibility and almost nothing to do with discipline.

Sadly there is now no name for the idea that adults will be so committed to the potential of their children that they will keep refining and changing what they do until they see all their children succeed.

Nonetheless, this series provides a road map for what can happen when adults embrace such an ethos of responsibility.

Tune in tomorrow for Part One of the University Prep – Steele Street turnaround story

Doug – I’d love to know more about the chart you’ve shown. Coming from a UK perspective I’m not familiar with “Median Growth Percentile” – is this a measure of progress from an earlier start point?

Also, the chart seems to be showing results for 4th graders, so if I’m interpreting it correctly, the 15/16 and 16/17 results will relate to different cohorts of students rather than the same kids one year later? I have a feeling that my interpretation of the chart may be wrong based on lack of familiarity with the US system for measuring attainment and progress!

Whether it’s the same cohort or the next cohort down within the same school it still represents a dramatic improvement in standards and I look forward to reading more tomorrow about what actions the school took to achieve this!

You’re correct. it’s a comparison of different cohorts so it’s not exact apples to apples and that matters. That said the scale of the change is immense (basically they went from almost no one proficient to almost everyone) and the idea that a school that we assume cannot in fact often can is worth paying attention to- though it’s legitimate to see it as a hypothesis and not a conclusion