05.31.23Simple Tools Ben Katcher Uses To Keep The Big Group on Task (So He Can Work With a Small Group)

Scanning and getting those thank yous ready

Watered down instruction is a problem in American classrooms. TNTP’s 2018 white paper, The Opportunity Myth describes the scope of this problem. The average student “spent more than 500 hours per school year on assignments that weren’t appropriate for their grade and with instruction that didn’t ask enough of them—the equivalent of six months of wasted class time in each core subject.” TLAC team-member Jack Vuylsteke shared some observations about a lesson that provides some pieces of the solution.

In the post-pandemic era, when more students are farther behind, teachers are more and more often asked to answer the question:

How can I make sure everyone succeeds by giving them extra support rather than simplifying the tasks we ask of them? How can I do this in a classroom full of students of a variety of levels of preparedness

Answering this question is essential and one solution is to work with smaller “pull-out” groups. But of course doing that poses a risk. What if the rest of the class loses its focus?

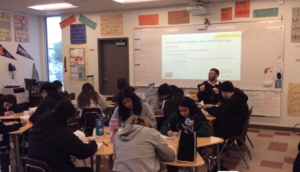

Ben Katcher demonstrates a few keys to solving this challenge in his AP US History class at Valor Academy in Los Angeles. We see that Ben has his students divided into small groups for a task; one group has been strategically placed in the front of the classroom because Ben knows these students will need a bit more of his support.

Ben provides students with clear directions and allows them to begin working together on a challenging task. Students know how many statements to generate, where to record them, and that they’ll share those thoughts to the rest of their classmates in a few minutes. Establishing this clarity is a crucial step to generating student autonomy– otherwise, Ben likely will have to answer task-based questions– “Where should we write this?”– for the next four minutes instead of helping his target group develop their analysis. His students are prepared to work independently.

After giving these directions, Ben immediately takes a seat with his target group—the students who need a bit more support. Notice that he has purposefully chosen to position his chair to face outward towards the class– he can see every student in the room from that seat. His group is in the middle of the room where he can see the rest of the class clearly. His chair is placed there in advance in exactly the right spot. He doesn’t need to drag a chair over and squeeze in. The transition is seamless. He sits down in perfect position right away.

As soon as he sits and prepares to start working with the students in this group, he uses the Be Seen Looking technique, visibly scanning the room with his eyes in a slightly exaggerated manner, even swiveling a bit to get a clear picture. He wants the students in other groups to know he’s observing them. Knowing he sees them will help them stay on track. As he does this, he then Narrates the Positive, quickly describing and appreciating a few examples of on-task behavior. Students like Evelyn and Crystal are starting right away. He quickly thanks them for that maturity and autonomy and gets to work with his target group.

Roughly a minute later Ben repeats this behavior: We see him roll back in his chair and stretch a bit to scan the room. He wants students to know he’s observing. The more clear that he is looking the better. What he finds is that students are continuing to focus on the task, so Ben subtly narrates his appreciation– “I see everybody doing what they’re supposed to do, which makes me really happy.” This is preferable to overcongratulating them— which might make it seem like he was surprised— or ignore them—which might make it seem like he wasn’t watching.

His tone towards his AP students is quiet and reserved, definitely not over-the-top and OMG so excited. It’s just enough to appreciate and demonstrate that he’s looking. “Thank you,” he says, and then describing the level of effort in the room: “It’s a beautiful thing.”

We agree, but it’s certainly no accident. The sublime—an optimal learning culture—is accomplished in part by Ben’s attentiveness to the mundane: he’s positioned himself to see the class; he scans regularly and visible so students know he cares about and will see what they do; he notes their productive work when he sees it. Ben helps a “beautiful thing” become a reality by being an intentional and consistent in attending to the details.