07.19.21Quotes and Quotability: A Brief Notes on a Lost Idea

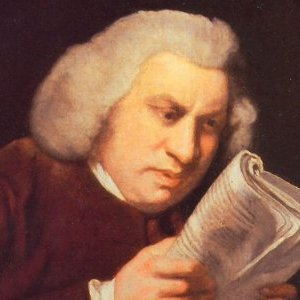

On the reading front, I’m currently finishing Leo Damrosch’s The Club: Johnson, Boswell and the Friends Who Shaped and Age. It’s a group biography of Samuel Johnson, James Boswell and their circle, which included Adam Smith, Edward Gibbon, Joshua Reynolds, Hester Thrale and David Garrick.

Damrosch’s description of Johnson’s death is both poignant and interesting. Johnson is surrounded by friends and knows he’s dying even though the doctors try to tell him otherwise. And so much of his communication is epigrammatic: couched in quotations from texts that Johnson knows well and knows his friends also know well.

A doctor comes to see Johnson and Johnson quotes from Macbeth:

Canst thou not minister to a mind diseased

Pluck from the memory a rooted sorrow

Raze out the written troubles of the brain…

The lines are Macbeth’s- incongruously asking his own doctor to minister to his mind not his body when he (Macbeth) is being driven to madness and illness by guilt. Johnson, plagued by depression all his life, is alluding to his own psychological angst amidst (and contributing to?) an ailing body. He is referencing the ‘diseased’ mind’s inevitable downward pull on the body, his own sense of despair and the universality of this feeling (given that Shakespeare wrote about it and so many have thought about those famous lines). In other words being able to quote the play makes him able to evoke the scene and allude to far more than just the words say. It allows him to communicate in stories in a sense. Simply being able to communicate all of this gives Johnson comfort.

But the doctor goes one better. He replies in kind to Johnson using the words of the doctor replying to Macbeth in the play

“Therein,” he says, “the patient must minister to himself.”

He is affirming his understanding of Johnson’s plight and affirming the value of the things Johnson values even while he reminds him that the answer is no. Johnson, Boswell notes, “expressed himself much satisfied” with the doctor’s response.

The doctor by affirming his knowledge of the quotation says: we know the same stories, you and I, we speak the same language. And this is enough to both comfort and please Johnson and to affirm that they have communicated on an enriched basis.

Quotations served this purpose throughout the lives of citizens of the 18th century. To quote a text was to borrow wise words and allude to a context in a well-known story and affirm a connection among individuals: we have shared stories between us; this makes us kindred. They were profoundly important and people quoted to each other constantly.

Which of course we hardly ever do today–some younger folk do a version of this by quoting movie lines to one another, which I think serves many of the same purposes–and one reason we don’t is because we don’t know any quotes. The last thing on Earth most English teachers would do would be to ask students to memorize a few passages from the books they read. But oddly doing so would be profoundly powerful. The quotation evokes the context and the argument and brings the whole thing to life even if just in your inner dialogue. And from a student’s perspective there’s not much more powerful you can do in writing a paper than quote an author and allude to a scenes and context more broadly.

In our Reading Reconsidered English Curriculum we often insert a handful of key quotations in the Knowledge Organizer for exactly this reason. Knowing a memorable quote allows you to allude to the themes and ideas from a great book in a rich and tidy way–to yourself and to others.

Much like Johnson and his doctor.