04.25.24My England Travelogue Part 2: Blaise High School, Bristol

Nabarro: Re-setting a culture is no small thing.

A few days ago I started a blog travelogue about my week in England with a summary of my trip to Ark Soane Academy in London.

The next day, Wednesday, I was in Bristol to visit Blaise High School which is a fascinating and impressive case study in turnaround. When the current leadership Greenshaw Learning Trust took over it had a minus 1.4 Progress 8 score. Lessons were constantly disrupted. It was hard to teach and it wasn’t a safe or supportive environment for students.

In the span of under two years they’ve brought Progress 8 scores to .-2.

Obviously the goal is to turn the cultural turnaround into even stronger academic outcomes and interestingly that often requires a different set of moves and priorities. Now that real teaching is happening that’s a legitimate goal. I think they’ll do it.

But first let me reiterate what should be obvious but isn’t, somehow: how nearly impossible it is to make academic progress when the culture is broken; how incredibly difficult cultural turnaround is—it’s much easier to start a school than to fix one.

There were so many details of how this was accomplished. Morning arrival is a good example.

Teachers were stationed outside the school. Not just inside the school’s gates but out on the pavement in the areas where students approached. Teachers would greet students warmly and by name (you are known here; we care about you) but would also often “fix” small problems with uniform or a reminder about phones, say, or just check in with students who looked “off” emotionally.

The result was that when students entered the school grounds they were already on the upswing. Their phones were away, they had already been reminded that the school cared about them and that expectations were a little higher inside those gates. This also gave school staff the opportunity to greet and talk to parents both their own and, interestingly, those from the local primary who often walked by as well. When those students enroll it will feel like a much more welcoming place.

Inside the gates a bright digital clock, visible from far away, was mounted on the wall of the school so it was easy to meet the expectation of punctuality. There was a room off the entry court where students who needed a belt or shoes or a tie for their uniform could get one simply and easily before school started. Unless it was a chronic issue school head Nat Nabarro said, the items were simply given to students without sanction. “We care about you but we expect things of you here.”

During this time students mingled freely and chatted inside the gates. Then, on signal, they lined up by class. Teachers worked the rows greeting students and ensuring they were ready for the day. Some of the teachers were simply masterful at striking just the right balance. You want to show warmth and caring but you are not their friend. You speak for the school and what the school does is very, very important.

A teacher then addressed each year group with greetings (it was the first day back from half term) encouragement and reminders. The school provided them with small stools to step up on so they could see and be seen (and heard) more clearly. First time I’ve ever seen that detail. Brilliant.

Each of these small pieces might seem tiny but together they add up to a cultural sea change and a coherent message. Especially (well, only) when they are matched by similar intentionality inside the school building.

It’s been a massive turnaround already and we should never dismiss or underrate how hard this is to accomplish.

Now the question is what comes next.

One thing we talked about was letting the students who are more bought in—those who (often) silently appreciate the change in culture to one that values their time and their learning and makes them safe–show their buy-in a bit more and a bit more intentionally.

The start of lessons is a great example. You could argue that the start of a lesson is almost always a norm-setting or -reinforcing moment. We signal or remind people of what the norms are. And as Peps McCrea points out the individual’s perception of the peer norm is the greatest single influence on behavior and motivation.

So the start of class is important for the social signals students send to each other.

In an environment where behavior is uncertain and can easily go off the rails, you might start class very carefully, with direct instruction a fair number of cold calls and perhaps more limited opportunities for student interaction. The primary mode of student interaction might be mini-whiteboards, say.

Nothing wrong with this but the mini white board is safe—the safest way to ask students to be involved in lessons—and quiet. It’s easy to come to rely on it. So too cold calling.

But when culture shifts, a school might want to set a norm of more active and willing engagement in lessons.

In a vibrant Turn and Talk where the room crackles to life when the question is asked, for example, participating students send a message to their peers—I am all-in for this class—and when the majority of the class does it, it becomes a norm shaping moment.

Similarly Cold Call- an excellent but also lower-risk way to involve students. Teachers should use it. But also recognize that a moment when lots of pupils raise their hands is a norm-signaling moment.

To raise your hand sends a signal to the teacher—I’d like to speak—but also to one’s peers—I care about this topic and my learning enough to want to answer. When you sit in a classroom and see a sea of hands you get a very strong norm signal. We are all all-in.

Interestingly it is often, in my experience, the more experienced teachers, the ones who’ve been a part of the previous culture, who know what can go wrong, who are most cautious about the change. They know what they risk losing if they go too far.

Blaise has been really thoughtful about the process of managing this transition. There were some exceptional lessons and some very good but slightly more cautious lessons.

But I saw some beautiful examples of teachers challenging themselves to immediately incorporate ideas from professional development. The prior week’s focus had been Active Observation and I observed as Nancy Jessiman not only taught a brilliant and rigorous lesson that students willingly engaged in, but immediately put the contents of PD to work. Asking students to write the definition of a scientific term, she had them write in their notebooks rather than on MWBs and then circulated, making comments as she went that both reinforced learning (“Excellent, John”; “Don’t for get to use the term oscillation, Sarah”) and built relationships with pupils.

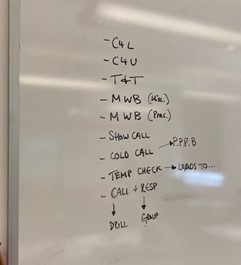

And one other tiny moment that stuck with me. On the back board in Josh Mazar’s maths class I noticed this:

It’s his “show flow”—the means of participation he intends to use in the course of his lesson. It’s a thing of beauty in my mind. First it shows preparation. He’s thought through in advance not just what content he’ll cover and what questions he’ll ask but how he’ll ask students to answer: a turn and Talk followed by two uses of mini white boards and then a Show Call, for example. Second he’s made this visible to himself throughout the lesson. Could there be a better way to remind himself of what he wants to do and to help him manage the load on his working memory.

One of my biggest personal takeaways from my new life on zoom, which started during the pandemic but is now part of all of our lives, was the power of small icons. I put them at the bottom of my slides to remind myself when to use the chat function or cold call or, as this icon reminds me, to use break out rooms:

![]()

It’s such a calming support to always know what move I’d planned. I can just glance at it to be reminded. Almost no one else knows what it means-it’s in code—but even if they did, so what.

The show flow on the back board is a brilliant version of the same idea for inside the classroom. It’s on the bac wall where he’ll see it easily as he looks at students. They can’t see it because they are looking at him but even if they did it’s mostly in code. And so it’s easy for him to stay on plan. Which makes building a plan more worth the time.

As a side not and small digression there are lots of similar ways teachers can use the back wall for coded reminders to themselves: a smiley face to remind yourself to smile, say. Or the letters NTP if you’re trying to remember to narrate the positive. Coded visual reminders in the classroom are gold for a teacher whose got a complex task and a room full of 30 students to manage.

Anyway, my visit to Blaise was a pleasure and a reminder of how critical it is to invest in getting the culture right. And then not be afraid ot make changes when you’ve begun to win that challenge.

Thanks to Nat and his amazing staff for opening their doors so completely.