01.23.20Lessons: I Thought I Hated Science Fiction Until I Read it Through Emily’s Eyes

Just this week we finished up our Science Fiction unit for our reading curriculum. It was designed and written by Emily Badillo and includes 8 classic short stories with lots of fantastic knowledge building and writing opportunities.

I’m going to tell you a little bit about the unit. And then at the bottom I’m going to tell you something even more important that it reminded me of.

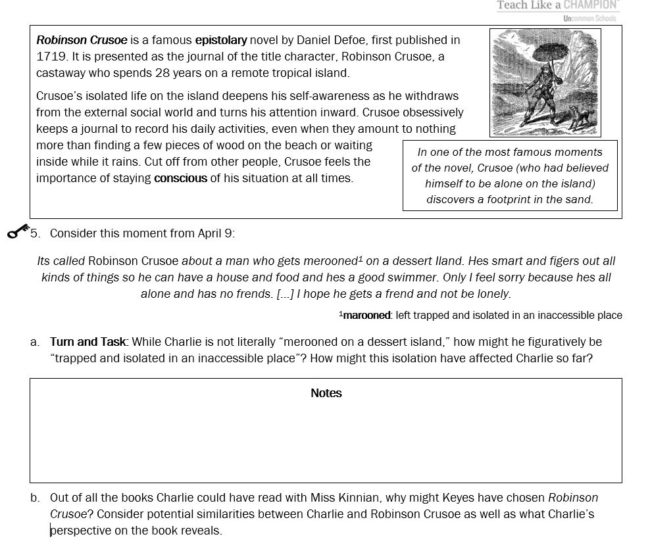

Fantastic knowledge building and writing opportunities: There’s this question about the scene in ‘Flowers for Algernon’ where Charlie is given a copy of Robinson Crusoe to read. The moment is full of symbolism to analyze… if you have the background knowledge to engage.

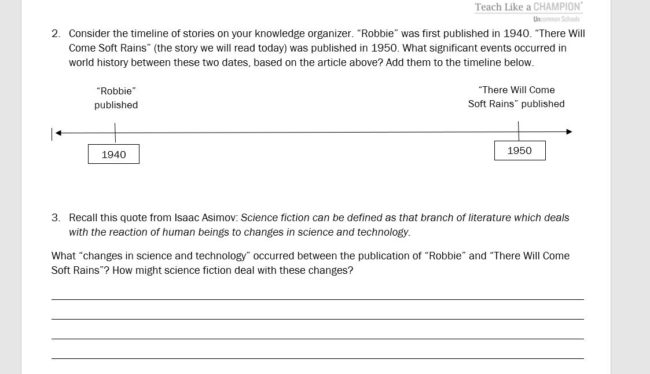

One of the best parts of the unit is the way Emily engages history. Science Fiction is often a reflection of anxieties about current issues in society, she notes in an early lesson, and so the unit, with stories written as early as 1940 (“Robbie”; Isaac Asimov) and as recently as 2016 (“The Great Silence”; Ted Chiang) becomes a study of Cold War worries about nuclear war and totalitarianism as much as machine intelligence and space travel.

I thought this question from early in the unit was a great example of ‘grounding’ the texts in history. “There Will Come Soft Rains,” as some readers will know, is a post-apocalyptic Ray Bradbury story about a mechanized house that–alone–survives a nuclear attack. Here Emily asks students to consider the date of its authorship as compared to Asimov’s optimistic story “Robbie.”

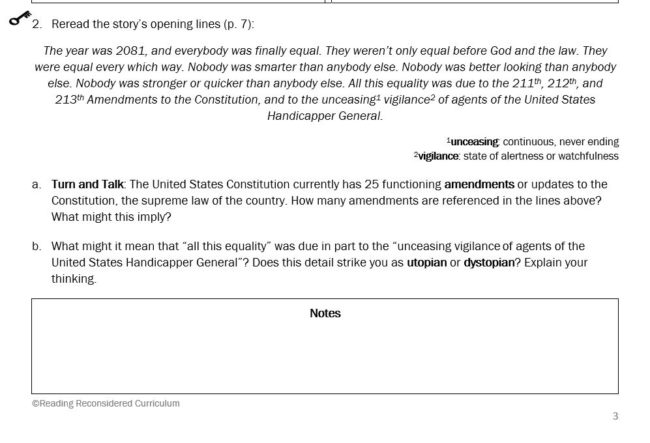

There’s also lots of great close reading, as in this example from the opening of Kurt Vonnegut’s ‘Harrison Bergeron.’

Something even more important that this reminded me of: The most surprising part of the unit was how much I enjoyed it, which I mention because I have always disliked the genre of Science Fiction. I have spent most of my reading life not only avoiding reading it but–honestly–scorning it a little. It always struck me as consisting mostly of hyperbole, over-written prose and imaginary space weapons in made-up worlds. But when I read it through Emily’s eyes, I realized it is not that way at all. I loved the unit in part because the stories were so relevant and connected in ways I had not expected.

I mention that because there’s so much valorization of choice in ELA circles. The argument that kids will love reading if only we can just let them read what they love is epidemic. The choruses of Let Them Choose! resound through the profession.

But the flaw in this argument is that people choose based on limited information and false conceptions. If that’s true of me–a 50-year-old former English teacher with a BA and a masters in English Lit–it’s probably true of a 14 year old who’s read 20 or 30 full length books in his life and has never heard of the book that is destined to change his perspective forever.

We are wrong about what we like. We know too little. And then someone like Emily lets us see it through their eyes and it comes to life. Times ten when allowing for choice means everyone is reading their own book on their own and never hearing other people’s unexpected interpretations. Loving a book you had not expected to like is in many ways much more powerful than reading a book you expected to like and which you’ve already read 3 similar books to in the series. Student choice for independent reading in nice, but teacher choice of books read by the class is a gift to students. It expands, rather than confirming their perspective.