09.23.21Kate Jones: Exit tickets, Performance & Long Term Learning

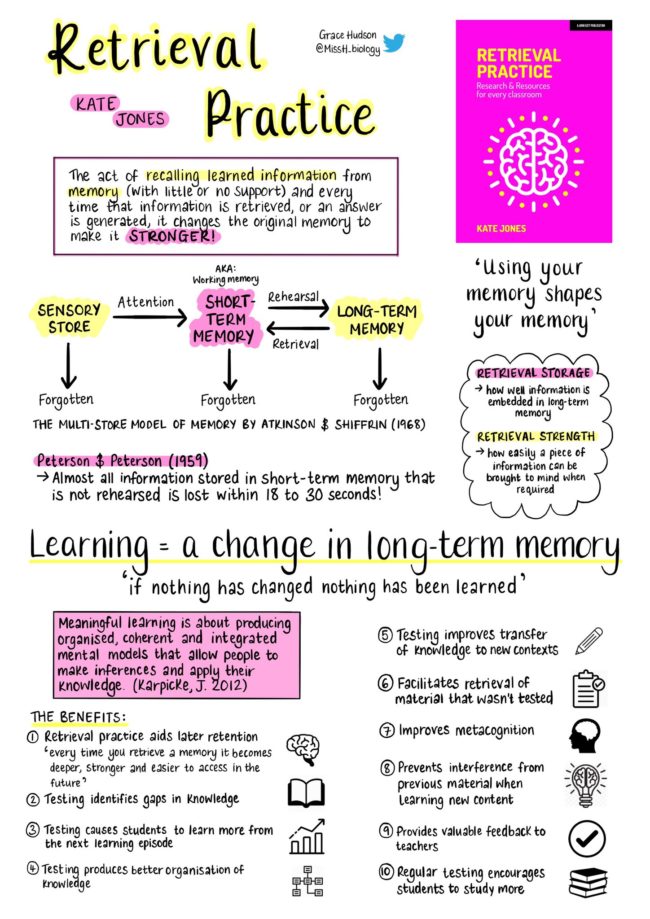

Graphic by Grace Hudson (@MissH_biology)

A few weeks ago I co-wrote an article with Kate Jones on the idea of retrieval practice questions. After some further conversations Kate shared this new reflection on how to use exit tickets to build long-term memory and learning.

Inspired by a recent conversation with Doug on Teachers Talk Radio, I have been reflecting on how exit tickets can be used at different points in the learning process. Exit tickets have been widely used in classrooms due to their simplicity, ease and usefulness as a formative assessment technique. However, it is important for teachers to understand the specific purpose they serve and what information they provide.

Exit tickets consist of one to three questions (or problems) that students answer at the end of a lesson that the teacher can collect quickly and easily. They are deliberately short, clear and concise, intended to hone in on and assess understanding of the main points of the lesson. Exit tickets can provide useful data and insight for teachers about what students understood (or struggled to understand). However, it is important for teachers using exit tickets to be aware of the distinction between learning and performance. Based on their research findings professors Robert and Elizabeth Bjork have written extensively about this distinction. Performance demonstrates whether to-be-learned knowledge or skills can be produced during the instruction phase itself, which can be evident via an exit ticket but this is not always a reliable indicator of learning, which occurs when there is a change in long-term memory. The Bjorks argue that what teachers can measure during the instruction process, in a lesson, is performance but not (yet) learning.

Performance can be dependent on recency and cues that are present during the lesson but are unlikely to be present at a later time in a different context, when some skill or knowledge is required. Bjork and Bjork (2009) write that “information coming readily to mind can be interpreted as evidence of learning, but could instead be a product of cues that are present in the study situation, but that are unlikely to be present at a later time. We can also be misled by our current performance. Conditions of learning that make performance improve rapidly often fail to support long-term retention and transfer, whereas conditions that create challenges and slow the rate of apparent learning often optimize long-term retention and transfer”. The implications of this with exit tickets is that the end of a lesson is a good time to check for understanding. Misconceptions and misunderstandings can be highlighted with exit tickets, informing and guiding future planning for the teacher. But this is not to be confused with long term learning.

Exit tickets at the end of a lesson will not tell or show teachers if that information has been transferred to long term memory and can be recalled from long term memory. To do that it is necessary to revisit the questions or problems at a later date to find out what students can recall because, as Kirschner, Sweller and Clark (2006) stated; learning constitutes a change in a student’s long-term memory and capability.

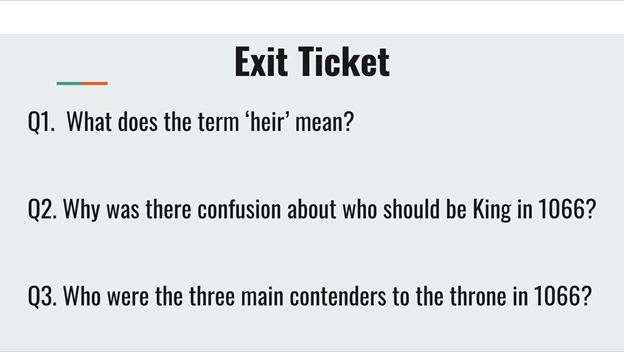

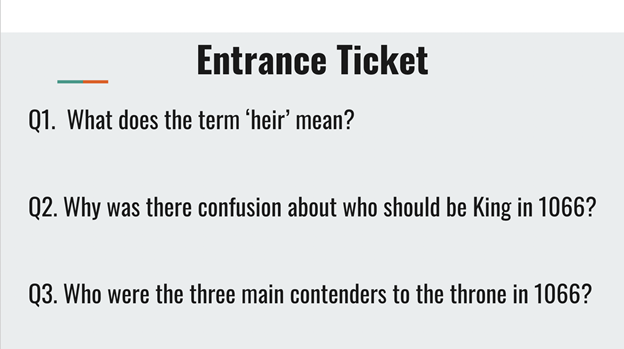

In order to do this, teachers must allow some time for forgetting and revisit the exit ticket questions or problems again at a later date. Exit tickets can be recycled into an entrance ticket, ideal for a ‘Do Now’ task at the start of a lesson. The same questions and problems can be posed (or adapted) for students to answer from memory. This will allow students the opportunity to recall information from prior lessons and the exit ticket is being used at this point to assess long term learning.

Another important factor to consider: explaining to students why the questions on the exit ticket are being repeated. This helps students themselves grasp the distinction between performance and learning. If students know they will be asked the same questions again in a different lesson, this can further add to the low stakes nature of retrieval practice. Students may even rehearse the information and test themselves, knowing they will be asked those questions so that they are in a stronger and more confident position to recall information from long term memory. Students that might tend to rush answering questions on an exit ticket, as they focus on leaving the lesson will have to ensure their focus is on the exit ticket; as they will be expected to recall this information again at a later date.

Exit tickets can include questions that aren’t based on the content of that specific lesson but instead asked questions based on material previously covered, as a retrieval opportunity in contrast to checking for understanding. Questions from a previous exit ticket could be recycled and repeated once some time has passed.

The example below allows the same template and same questions to be distributed to students. It also illustrates to students the importance of the lesson content and that it shouldn’t be forgotten once the lesson is over. Exit often implies the end but actually an exit ticket is used in the early stages of the learning process.

Another idea is to have students compare and contrast their responses from the exit and entrance tickets; do the answers vary or differ in terms of accuracy or depth? This can further illustrate the impact of forgetting on learning. The additional benefit of using exit tickets as entrance tickets is the workload implications for teachers by reusing the same resource with their classes.

A carefully designed exit ticket can be used at different points in the learning process, checking for understanding (performance) and later allowing an opportunity for recall (learning).

Thanks to Professor Robert Bjork for checking the accuracy of this post.

References:

Why Minimal Guidance During Instruction Does Not Work: An Analysis of the Failure of Constructivist, Discovery, Problem-Based, Experiential, and Inquiry-Based Teaching. Paul A. Kirschner, John Sweller & Richard E. Clark. (2006)

Elizabeth L. Bjork and Robert Bjork Making Things Hard on Yourself, But in a Good Way: Creating Desirable Difficulties to Enhance Learning (2009)