11.19.19How People Learn Best: Learning Styles vs. Dual Coding, a Guest Post by Benjamin Keep

Recently I wrote a post about Learning Styles and why teachers held fast to their belief in them, even in the face of convincing evidence that they are not only hogwash but counter-productive. Several people responded including Benjamin Keep who works with Ulrich Boser at his organization the Learning Agency which uses the science of learning to help organizations succeed. Much of their work focuses on an idea called Dual Coding, a scientifically validated concept that puts what seems compelling about learning styles to practical use. Ben wrote this helpful post comparing the two.

If you look on any social media platform, you’re likely to see references to learning styles about as often as you’ll see pictures of adorable puppies. They’re both almost impossible to avoid.

One typical learning styles quiz on Buzzfeed explains what it means to be a ‘visual learner’ or a ‘tactile learner’ and then asks people which style works best for them. Choose your favorite!

But no matter where you look on Buzzfeed and co, there are no quizzes about Dual Coding. Which is unfortunate. Because learning styles and Dual Coding have a few things in common, and while learning styles is an extraordinarily widely believed myth about how we learn, it’s Dual Coding that has the strong scientific backing and immense practical applicability for teachers. One idea has all the substance; the other gets all the clicks.

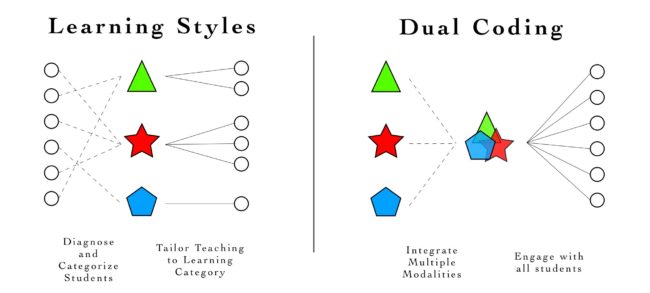

Dual Coding is the idea that presenting information in different formats can accelerate learning. Learning styles is the idea that people have a preferred way of learning and will benefit if we can just frame things in their chosen style. They’re easy to confuse. But in fact they’re saying almost diametrically opposed things. Learning styles says: “Teach individual students through their preferred modality.” Dual coding says: “Present material carefully in multiple formats to teach all students.”

Dual Coding

“Dual coding” is shorthand for several related learning effects but the simplest idea is that integrating text and visuals together, when done right, can accelerate the process of learning new information, especially when students do one then the other rather than trying to process images and visual text simultaneously. Further, Dual Coding tells us that providing multiple visual representations of an idea helps students understand concepts more deeply, and apply the material more flexibly.

Research also suggests that combining visuals with text (or visuals and audio) is a way of expanding our working memory limitations. Our working (or short-term) memory system can only process a limited amount of information at once. Specific modalities seem to have their own limits, too. Packing information only through text or only through visuals doesn’t make full use of our available working memory “channels.” But dual coding strategies do.

Evidence of the effectiveness of these particular strategies flow from research on human memory and the transfer of knowledge to novel problems. And they all come with a very large caution sign attached to them.

Like many effective learning strategies, dual coding is about managing student attention. And students’ attention spans, just like yours and mine, are severely limited. If an attention span is a highway, there’s only so many cars that can fit on it without causing a traffic jam. Dual coding lets us make use of all of our available “lanes,” but cram too many cars on it and we’ve still got problems.

In other words, designing effective “dual coded” materials requires paying attention to many (very real) student differences. Prior knowledge, for example, widens our proverbial lanes. Students with high prior knowledge can make sense of several different representations of a phenomenon and walk away enlightened. Students with lower prior knowledge are more likely to get bogged down without knowing vocabulary and the visual cues necessary to interpret the very same presentation.

Using dual coding effectively also requires paying attention to the material itself. When designing any instructional materials, we have to make decisions about what to include and what to leave out. The more you leave out the more students can focus on the important ideas and see the forest through the trees.

Another thing to consider is how much freedom your students will have as they work with the instructional materials. Some of the strict trade-offs in instructional design found in controlled, laboratory settings (where students have little control over how they integrate instructional material) do not seem to hold when students have more freedom to manage their attention.

So: integrating modalities like visuals and audio is, generally speaking, a good idea. There is, however, another way of thinking about modalities that has wormed its way into our brains: learning styles.

Learning Styles

When people hear that learning styles don’t exist, they get defensive (see the comments to this video). A common rejoinder goes something like: “Of course learning styles exist! Students aren’t all the same!” When psychologists argue that learning styles don’t exist, however, that’s not what they mean.

Students aren’t all the same. That much is true. But learning styles goes beyond saying that. Learning styles says that providing a student with a learning experience consistent with the student’s style disproportionately improves their learning over an experience that is inconsistent with the student’s learning style.

There’s a relatively simple way of testing the learning styles idea: diagnose students’ “learning style,” then see if teaching students in their preferred style helps them learn more than teaching the students in a non-preferred style. When researchers do this, they don’t see any advantage of the preferred learning style. There’s little evidence that learning styles “works” and lots of evidence that it doesn’t.

The kinds of student differences that do affect learning are more nuanced than the idea of learning styles would suggest. But, as we discussed earlier, modality is not completely irrelevant to learning either: integrating modalities is a particularly powerful way to learn.

My takeaway? If it’s on a lot of Buzzfeed quizzes, it’s probably bunk.

Benjamin Keep is an advisor to the Learning Agency. He blogs at www.benjaminkeep.com and through Medium.