04.30.24How Madi B. Puts Error Analysis At The Center Of Student Learning

Engineering student success.

In this second post on our work on math achievement with schools in the Memphis School Leadership Collaborative (MSLC), Joaquin Hernandez shares some of our learning from one of the champions of the MSLC, 8th grade teacher and instructional coach at Memphis Rise Academy, Madi Bienvenu.

Closing Gaps Via the Do Now

The centerpiece of our work with teachers and leaders within the Memphis School Leader Collaborative is a research-informed Lesson Delivery Model (LDM). We define this as a content-specific pedagogy document that defines how a math lesson should unfold. The Math LDM we developed follows a gradual release model, which is informed by Rosenshine’s Principles of Instruction, as well as findings from Cognitive Load Theory, such as the Expertise Reversal Effect.

In our experience, math curricula often provide teachers with an Exit Ticket, or similar end-of-lesson formative assessment. However, teachers are also left without much direction on where and how to address misconceptions from the previous lesson. So, as part of our LDM, we codified guidance on how MSLC teachers can prepare and execute a variety of Do Now activities—such as retrieval practice, fluency, or Error Analysis—that are responsive to formative data like Exit Tickets or quizzes. Throughout this post, we’ll share how one MSLC teacher leveraged our guidance for Error Analysis Do Nows to address common errors that surfaced on Exit Tickets.

See It in Action: Madi Bienvenu

To kick off our exploration of Error Analysis Do Nows, we’d like to spotlight Madi Bienvenu, an 8th-grade Algebra I teacher and instructional coach at Memphis Rise Academy. In 2023, Madi achieved the third highest proficiency rate on the Tennessee state exam out of 69 Algebra I teachers across Memphis Shelby County Schools. In this clip, you’ll see Madi lead an Error Analysis Do Now, in which she has students analyze a common incorrect answer from a recent Exit Ticket. As they study the work, students are prompted to explain in writing what’s correct in the work and, importantly, what’s incorrect and why. What follows is a brief discussion of the error, a stamp that ensures kids capture the key takeaway from the error, and another at-bat with a similar problem.

With that, here’s Madi’s classroom:

There were a few things we loved about Madi’s teaching in this clip:

- Culture of Error: Madi makes it safe for students to study and learn from this mistake through her tone and words. For example, Madi acknowledges that the work they’re studying contains a common mistake, which normalizes error. When discussing the error, she exudes calm and warmth, signaling to students that errors should not be a source of anxiety or frustration. In her eyes, they are a normal–and even valuable–part of learning. What’s more, Error Analysis is not a one-time activity, it’s a routine part of Madi’s lessons. This is why students don’t seem phased by it: they engage actively and earnestly in the discussion without defensiveness or hesitation. Finally, Madi’s use of universal language like “we” or “our” further normalizes error and emphasizes that learning from mistakes is a shared endeavor.

- Study Why: Madi asks students to identify the error and explain why it’s incorrect (“Why is -7 also a part of the solution?”). This helps students who initially got it wrong to better understand their error, which in turn helps them avoid making the same mistake next time. It also causes students who did get it right to deepen their understanding through elaboration and explanation. This deepens students’ learning and makes it more durable (Siegler, 2002).

- Means of Participation: Before students discuss the work, Madi first gives them an opportunity to independently study and process it in writing. This elevates the quality and breadth of student participation during discussion. In addition to Everybody Writes, Madi maximizes academic engagement with techniques like Turn and Talk, Volunteers, and Cold Call. We also noticed that she intentionally sends kids into a Turn and Talk to identify the error (Question #2). This is critical, as students won’t be able to engage in a productive discussion of the error if they don’t perceive it.

- Active Observation: As Madi circulates, she observes students’ work, collects data on student thinking, and plans who she’ll Cold Call to support the discussion. Examining students’ work also allows her to check whether students are on the right track, so she can intervene with timely feedback if they aren’t.

- Stamp the Learning: Madi asks students to distill the key takeaway from the discussion into one tidy, written statement with the prompt “Remind me….” This helps students avoid making the same mistake when they encounter similar problems (like the very next one!). Additionally, the simple act of having students write the stamp helps them encode it into their long-term memory and equips them with a resource they can refer back to when they encounter similar problems. Finally, we appreciated how she had students fix their work, ensuring they also leave the discussion with an accurate solution.

- Additional At-Bat: Madi immediately follows the stamp with an opportunity for students to apply their learning to a similar problem. This allows Madi to assess whether she successfully closed the gap, help students cement their improved understanding, and give students a chance to ultimately get it right.

Engineering Materials For Student Success

In studying classrooms like Madi’s, we realized that one of the hidden—and often unheralded—drivers of successful lessons is intentionally designed student-facing materials. As you’ll see below, Madi carefully designed this Do Now to maximize engagement, rigor, and mastery. Here were some of our biggest takeaways from how she structured it:

One of the biggest potential impediments to the success of Error Analysis is a finding from Cognitive Load Theory known as the Transient Information Effect. This occurs when students are temporarily presented with information, say in the form of text or written work, and then asked to try to recall it from memory. By embedding the problem and response directly in students’ Do Now, Madi avoids overloading students’ limited working memory, and instead enables them to devote precious cognitive resources to actually analyzing the response. This is also why we love how she includes the “stamp” and “at bat” in close proximity to the incorrect work. By keeping all of these components together on the same page, Madi makes it easy for students to do the thinking work that’s required and to successfully apply their learning.

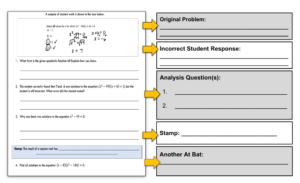

While the content of Madi’s Error Analysis Do Nows changes from lesson to lesson, she holds the following elements constant (below):

After sharing this Do Now structure with MSLC leaders, educators at Leadership Preparatory Charter School in Memphis created a template their teachers could use to plan daily Error Analysis Do Nows. We love this resource because it helps teachers ensure that the essential components of a successful Error Analysis Do Now are always present, regardless of the gap they’re addressing.

A Coda On Error Analysis

As we saw on display in Madi’s video, one best practice that our team codified and shared with MSLC teachers and leaders is Error Analysis, which we define as an activity that teachers use to help students study, unpack, and correct a common error from a recent Exit Ticket or formative assessment. This practice is rooted in research from Cognitive Load Theory on the benefits of asking math students to study Worked Examples or fully “worked out” solutions to problems. What’s more, research has revealed that it’s not only beneficial for students to study correct work, but also to study and explain errors in incorrect work. Specifically, Error Analysis has been shown to:

- Lead to deeper learning and to improve students’ performance with similar problems (Siegler, 2002)

- Strengthen students’ conceptual and procedural understanding, as well as their equation-solving abilities (Booth et al., 2013; Barbieri et al., 2020)

- Increase students’ long-term retention of knowledge (Rushton, 2018)

- Enhance transfer and improve students’ performance on application problems (Corral et al., 2020)

Another research-based variation of Error Analysis that teachers have had success with involves asking students to compare two Worked Examples—one that’s correct and one that’s incorrect. MSLC teachers have found that this can help students more efficiently notice the difference(s) between the two responses, which takes advantage of a phenomenon known as the law of comparative judgment. This exercise is a natural springboard for engaging class discussions about which answer students think is correct and why.

A Few Keys to Success

As Madi demonstrates, Error Analysis can be a powerful tool for addressing misconceptions and building a classroom in which students feel safe revealing and learning from mistakes. Here are some key conditions that can help teachers make the most of them:

- At the “Sweet Spot”: Error Analysis works best at the “sweet spot” of difficulty. On one hand students must have enough cognitive schema to be able to engage productively in discussion. If they don’t, they may leave the discussion even more confused about what the correct method or answer even was. On the other hand, if the vast majority of the class already arrived at a correct answer, then students may disengage and little learning will likely take place. One way to strike this balance is to identify a problem that a significant percentage of the class understood the concept but made a crucial mistake in the process. It’s also important to note that if most of the class had great difficulty with a problem, or there is no clear error trend, it can often be more beneficial for a teacher to re-model how to solve it, while narrating their reasoning as they go.

- Low-Stakes: Error Analysis can’t be a one-time event, or something you only do to address errors from high-stakes, cumulative assessments. It works best when you use it consistently and universally. Consistency is what builds psychological safety and increases students’ openness to reflection and feedback.

- Balanced With Other Types: Error Analysis Do Nows are just one type that teachers should have at their disposal. In our experience, they work best when they’re used strategically, and in balance with other Do Now activities, such as retrieval practice, analysis of correct Worked Examples, mixed review, fluency practice, and more.

- Avoid Hiding the Ball. As we’ve noted above, students can’t analyze an error they can’t perceive. That’s why, when you’re first using this activity, it can be helpful to narrow students’ focus to the most relevant aspects of the response that you want them to analyze. Instead of starting with a prompt like “What’s incorrect?” you might consider highlighting the particular step where the mistake occurred, naming the part that’s correct so students focus just on what’s incorrect (without naming the error), or even naming the error before prompting them to explain why that’s a mistake. As students build competence and confidence with Error Analysis, and develop mastery of the skills, you may choose to remove these scaffolds. By narrowing the focus to what’s relevant, you can help ensure that this activity is both productive and efficient.

A Final Note of Gratitude

We think Madi’s classroom is a great illustration of why, as legendary coach John Wooden put it, “the most crucial task of teaching is knowing the difference between ‘I taught it’ and ‘they learned it.’” By analyzing student work and being responsive to trends with routines like Error Analysis, she ensures her middle school students experience the satisfaction of grappling and succeeding with rigorous, high-school level content. We’re incredibly grateful to be able to learn from Madi, and so many teachers like her from Memphis and around the country. Thank you, Madi, for sharing your work!