11.20.18Cognitive Road Theory: Using Cognitive Load Theory to Teach My Kids to Drive

It was more or less like this…

I’ve been reading up on Cognitive Load Theory quite a bit lately. Two of my favorite discussions are this one by Adam Boxer and this one by the New South Wales (Australia) Dept of Education.

It’s been useful among other places in my personal life, where I’m in the midst of teaching two teenagers to drive. I thought it would be a good opportunity to write about how and why.

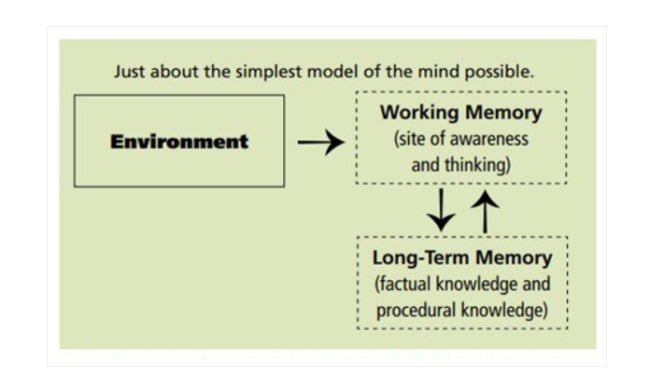

Cognitive Load Theory is about actively managing the level of demand we put on working memory while people are learning. Working memory is extremely limited. Asking too much of it slows learning and degrades perception. Not asking enough of it also slows learning and bores people. Cognitive Load Theory tells us that the key to mastering complex tasks is encoding component parts in Long Term Memory.

I want my kids to learn to be very good and very aware drivers. And I am totally inflexible about them learning to drive manual transmission, which probably isn’t worthy of notice to international readers but it’s rare in the US, where only 3% of cars have manual transmission.

Learning to drive manual is critical from a safety POV. Cognitive Load Theory helps explain why. It not gives you more control of your car and it teachers you to me more aware of the road by causing you to constantly interact with it and it makes you a more engaged driver because it requires more attention and interaction. An engaged, interacting alert driver is a safe driver.

But to shift, control the clutch, negotiate traffic and steer the car is a lot to learn at once. Trying to do that is a recipe for learning poorly and or slowly and not having enough working memory to focus fully on the most important task: perceiving the road environment.

Right now my daughter is just getting ready to learn and has actually never driven a car. But I am building her foundational knowledge and skills so that when she starts to drive she can focus more of her energy on important tasks like reading traffic. It’s actually easy to learn to be an un-perceptive driver. I am behind them almost every day.

My first step with my daughter is to get her familiar with gearing and how it works. I started working on this a few weeks ago. When we are driving together I have her do the shifting from the passenger seat.

It started with me putting in the clutch and saying, “First gear, please,” and then “Ok now second.” This is a pretty simple task and my daughter was pretty much able to do it right away. But there were a bunch of moments she had to work through some simple learning situations. “Am I in 3rd or fifth?” she’d say. Or she’d think she was in third but it would turn out she was in fifth. When she got this wrong it was no biggie because I was controlling everything else. The car didn’t buck or stall in an intersection. There was no fear of a disaster. She could just learn the task simply and without stress. She only had to learn one thing. Reducing stress is important. While she rarely made mistakes, she was often nervous that she would make one. As it was, with less to attend to she very quickly began to self-correct, to notice that a shift felt wrong and to fix it without my having to tell her. Again this was because she could focus all of her working memory on one task and therefore learn it quickly and well.

As she’s begun getting more familiar with gearing sequences I’ve increased the cognitive load. I’ll ask her questions. Slowing down I’ll ask, “What gear are we going to now?” And over time I’ve stopped telling her when to shift. Instead I tell her to listen for the engine. When you hear the RPMs fall you’ll know my foot is on the clutch. That means you should shift. This creates a new focus for her working memory- developing an ear for what it should sounds like to monitor the engine while she drives. These are two things she won’t have to think about when we take on the next step, which will be learning the clutch. She will know the gears and the sounds of driving before she sits in the driver’s seat and when she does she will have all of her working memory to focus on mastering one task.

A Model (Willingham’s) of the Brain Cognitive Load Theory Involves Managing the Load on Working Memory

We’ll start mastering the clutch just in our driveway (this is how I did it with my son). We’ll start with the difficult linkages of stop to first to second to first to stop. Then we’ll add reverse. Then we’ll add the rest of the gears. When that’s done we’ll start driving in a parking lot or a deserted road. By that point she will not have to spend her working memory thinking about clutch and gears and monitoring the engine. She can just think about road rules and decisions. She can use her working memory to observe. This is important. When your mind is on something else your perception is degraded. Try to make a left turn across traffic while adjusting your climate control system and you are several times more likely to have an accident. Then we’ll add other cars.

When my son and I reached this point (he now has his license) I would constantly try to focus on perception. Now that the complex task is near mastery I want to use Cognitive Load Theory to avoid letting Working Memory shift to autopilot. I want to keep in challenged and engaged. To do that I would focus him on problem solving in the perceptive environment: There’s a bike ahead. What should you do? Where should your eyes be looking as you approach this light? What might have told you that car was going to slow down like it did? Or we would out to a snowy spot and practice steering through a skid. Now my goal was to increase the challenge to ensure continued learning.

Anyway I thought this was a good example of how Cognitive Load Theory worked- both in using encoding of component parts of a task to learn it initially and then using challenges to continue the learning after initial task mastery.

We practice a variation of CLT in our 5th-grade junior journalism program; mainly, by not using computers. Working with notebooks and pencils (and later 8×11 paper and crayons) the kids are not burdened by the technical demands and challenges of the machine (keyboarding, spell- and grammar-checks, rebooting) which essentially sends them down the road faster than their immediate mastery needs will take them. And instead of using pre-determined page designs, the kids work with a basic template and 8 “essential elements” (name of paper, date, price, headline, byline, story text, picture, caption) to create some of the most endearingly creative front pages I have ever seen. Added plus: it’s great fun.