08.06.21Building a Culture of Error: A TLAC 3.0 Excerpt

Here’s another excerpt from the soon-to-be-released TLAC 3.0. The topic is building a Culture of Error and this portion deals with how this technique includes but is also broader than establishing psychological safety.

In a recent article about his development as a musician, the pianist Jeremy Denk observed a hidden challenge of teaching and learning: “While the teacher is trying to . . . discover what is working, the student is in some ways trying to elude discovery, disguising weaknesses in order to seem better than she is.”

His observation is a reminder: If the goal of Checking for Understanding is to bridge the gap between I taught it and they learned it, that goal is far easier to accomplish if students want us to find the gap, if they are willing to share information about errors and misunderstandings—and far harder if they seek to prevent us from discovering them.

Left to their natural inclinations, learners will often lean toward the latter. Out of pride or anxiety, sometimes out of appreciation for us as teachers—they don’t want us to feel like we haven’t served them well—students will often seek to “elude discovery” unless we build cultures that socialize them to think differently about mistakes.

A classroom that has such a culture has what I call a Culture of Error. Those teachers who are most able to diagnose and address errors quickly make Check for Understanding (CFU) a shared endeavor between themselves and their students. From the moment students arrive, they work to shape their perception of what it means to make a mistake, pushing them to think of “wrong” as a first, positive, and often critical step toward getting it “right,” socializing them to acknowledge and share mistakes without defensiveness, with interest or fascination even, or possibly relief—help

is on the way!

The term “psychological safety” is often used to describe a setting in which participants are risk-tolerant. Certainly psychological safety is a critical part of a classroom with a Culture of Error, but I would argue that the latter term goes farther: it includes both psychological safety—feelings of mutual trust and respect and comfort in taking intellectual risks—and appreciation, perhaps even enjoyment, for the insight that studying mistakes can reveal. In a classroom with a Culture of Error, students feel safe if they make a mistake, there is a notable lack of defensiveness, and they find the study of what went wrong interesting and valuable.

You can see this happening in the video Denarius Frazier: Remainder. Gathering data through Active Observation (technique 9), he spots a consistent error. As students seek to divide polynomials they struggle to find the remainder. Fagan is one of many students who have made the mistake. Denarius takes her paper and projects it to the class so they can study it. His treatment of this moment is critical. There is immense value in studying mistakes like this if teachers can make it feel psychologically safe. Unfortunately, it doesn’t take a lot of imagination to picture the moment going wrong—badly wrong. The student could feel hurt, offended, or chastened. Her classmates could snicker. Perhaps you are imagining the phone call that evening: Let me see if I have this right, Mr. Frazier. You projected my daughter’s mistakes on the overhead for everyone to see?

But in Denarius’s hands, the moment proceeds beautifully and, more importantly, as if it were the most normal thing in the world to acknowledge a mistake and study it. How does he do it?

First, notice his tone. Denarius is emotionally constant. He is calm and steady. There’s no suggestion of blame. He sounds no different whether he is talking about success or struggle. Next, he uses group-oriented language to make it clear that the issue they’ll study is common among the class. “On a few of our papers, I’m noticing that we’re getting an incorrect remainder . . .” he says. The mistake is ours; it’s relevant to and reflective of the group, not just the individual. There’s no feeling that Fagan has been singled out.

Another important characteristic of classrooms like Denarius’s has to do with how error itself is dealt with. It is best captured in a phrase math teacher Bob Zimmerli uses in the video Culture of Error Montage: “I’m so glad I saw that mistake,” he tells his students. “It’s going to help me to help you.” His phrase suggests that the error is a good thing. He calls the class to attention to show it is a worthy and serious topic, but he simultaneously normalizes the error through tone and word choice.

This is different from—the opposite of in many ways—pretending it is not really an error. Notice that Bob explicitly identifies the mistake as a mistake. His goal is to make it feel normal and natural, not to minimize the degree to which students felt they had erred.

I mention this because sometimes teachers struggle with this distinction. In workshops we occasionally ask teachers to write phrases that they could use to express to students the idea that it is normal and useful to be wrong. They sometimes suggest responses like “Well, that’s one way you could do it,” or “Let’s talk about some other ways,” or “OK, maybe. Good thinking!” These phrases blur the line between correct and incorrect or avoid telling students they are wrong. There are, of course, times when it’s useful to say, “Well, there’s no right answer, but let’s consider other options.” But that is a very different moment from the one in which a teacher should say something like “I can see why you’d think that but you’re wrong, and the reasons why are really interesting,” or “A lot of people make that mistake because it seems so logical, but let’s take look at why it’s wrong.”

You can see another example of this in the Culture of Error Montage. Mathew Gray, like Denarius, is sharing a mistake—this one made by a student named Elias (a Show Call, technique 13). He notes this right away: “Elias has made a mistake,” but he notes that this is not a surprise because he made the question difficult and that others have made the mistake as well. Then crucially he adds, “It’s a mistake that I made when I first read the poem.” He is the teacher and he, too, has struggled to understand. What could more fully contradict the idea that being an expert somehow means that one does not make mistakes? The idea is not to forestall defensiveness by making students believe they are correct, in other words, but to forestall defensiveness by helping students to see that the experience of making a mistake is normal and valuable.

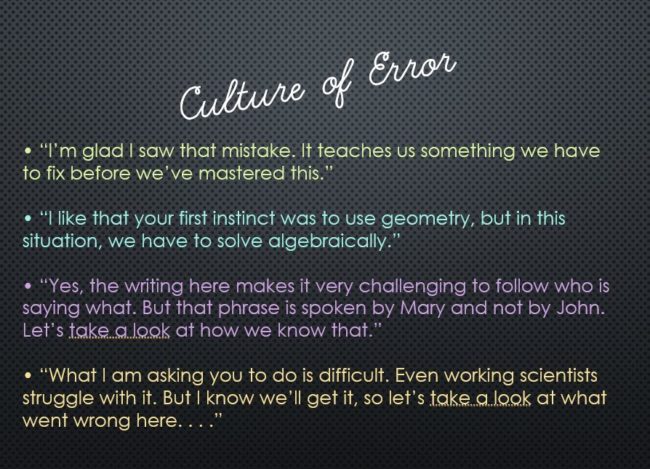

Here are some other phrases that do that:

• “I’m glad I saw that mistake. It teaches us something we have to fix before we’ve mastered this.”

• “I like that your first instinct was to use geometry, but in this situation, we have to solve algebraically.”

• “Yes, the writing here makes it very challenging to follow who is saying what. But that phrase is spoken by Mary and not by John. Let’s take a look at how we know that.”

• “What I am asking you to do is difficult. Even working scientists struggle with it. But I know we’ll get it, so let’s take a look at what went wrong here. . . .”

It’s worth noting that the statements are different. The first flips student expectation; the teacher is glad to have seen the mistake. The second gives credit to the student’s understanding of the mathematical principles—but makes it clear that she’s come up with the right answer for a different setting. The third and fourth acknowledge that the task is not the sort of thing you try just once and get right. They normalize struggle. As this Culture of Error is created, students become more likely to want to expose their mistakes. This shift from defensiveness or denial to openness is critical. As a teacher you can now spend less time and energy hunting for mistakes and more time learning from them. Similarly, if the goal is for students to learn to self-correct—to find and address errors on their own—becoming comfortable acknowledging mistakes is a critical step forward.

Es algo extraordinario ya que en el entorno en el que estaba me sentia con mucha ansiedad por cometer errores pero considero que ahora he aprendido más de ello que de mis aciertos.