05.25.22Beth Verrilli: Knowledge Based Curriculum Opens Worlds

If you’ve read this blog, or attended any of our webinars or workshops, you know that we believe in knowledge-based curriculum. Research shows that knowledge is a critical factor in learning to read, in building long-term memory, and in thinking critically. We’ve seen classrooms where knowledge encourages independent reading and where knowledge inspires wonder. Recent global events also reminded Beth Verrilli, who designs and writes units for our Reading Reconsidered English Curriculum, of other ways it is important. She shared this reflection:

If you’ve read this blog, or attended any of our webinars or workshops, you know that we believe in knowledge-based curriculum. Research shows that knowledge is a critical factor in learning to read, in building long-term memory, and in thinking critically. We’ve seen classrooms where knowledge encourages independent reading and where knowledge inspires wonder. Recent global events also reminded Beth Verrilli, who designs and writes units for our Reading Reconsidered English Curriculum, of other ways it is important. She shared this reflection:

In addition to its other benefits, knowledge also sets students up to better understand and interact with the world.

This idea has stood out to me in a couple of ways recently.

Over the past months, as stories of Ukrainian refugees have emerged, it’s made me think about one of our new curriculum units, Inside Out and Back Again. Thanhhà Lại’s novel-in-verse follows protagonist Kim Hà as she and her family make the painful decision to leave Vietnam after the fall of Saigon in 1975. With Hà as a guide, this unit allows students to delve into the refugee experience.

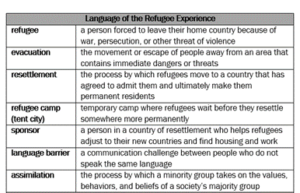

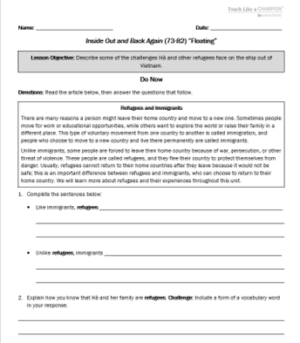

Over the course of the unit, students regularly interact with the concept of refugee. On their Knowledge Organizer, students learn language necessary to discuss the refugee experience, terms like evacuation and resettlement. In daily lessons, students probe the text to answer questions about the anguish of the decision to leave behind a beloved homeland and the practical and psychological issues inherent in assimilating to a new home. Nonfiction articles embedded into lesson plans throughout the unit explore concepts like grief, language barrier, and the difference between refugees and immigrants. These deepen students’ understanding of the complexity of the refugee experience. We also embed first-person narratives from other refugees to broaden student understanding of their protagonist’s fictional experience. We want them to feel compassion and empathy but also see themes and connections.

Similarly, a recent article about Afghan refugees reminded me of some themes from our new unit for I Am Malala. The article details the experience of Afghan women who were recruited as part of an elite platoon specially trained by the U.S. army to fight the Taliban, then evacuated to the U.S. last year after the fall of Kabul. Certainly, knowledge of the refugee experience allows deeper insight into this article. Many of the situations described in this article echo ideas students will grapple with throughout the course of the Malala unit: the importance of parents who believe in you; the strength to envision a role for yourself beyond societal restraints; the courage to put your life on the line for others; the psychological impact of war and trauma.

We can’t forget that the classroom prepares children for life outside of the classroom. We don’t teach students to read (or to solve math problems, hypothesize about chemical reactions, or understand the Declaration of Independence) just to be better students. Ultimately, we are grounding them in the knowledge it takes to be better citizens.

So centering curriculum around knowledge helps students become better readers, and helps them to grow into compassionate and knowledgeable adults—better suited to grapple with complex issues and more open to the perspectives of others.

The Knowledge Organizer from Inside Out and Back Again offers students language to talk about the refugee experience:

An embedded text ensures students understand the differences between refugees and immigrants.

A Summative Writing prompt from I Am Malala synthesizes students’ understanding of how Malala is shaped by her parents.