08.22.14Re-Post: A Teacher’s Review of The Giver

The film version of the Giver is out in theaters near you. To mark its release I thought I’d re-post my own review… of the book… as a teaching tool. Reviews of the movie version are mediocre but as a book it’s–to my eyes–a work of significance and ideal for teaching. Go to see the movie or don’t go to see the movie, but here’s my discussion of why you should keep teaching the book.

A few days ago I used a facebook post to ask folks what the best work of youth literature was. It’s an impossible question, of course and of course there were lots of fascinating answers and healthy disagreement. So before I provide my answer (as I promised I would) let me just say how great it is for all of us to be discussing the merits not just of how we teach reading but of which books we choose to do it with.

But anyway, here’s my answer. I should note that I explicitly limited myself to books written specifically for younger readers (aka “youth fiction”). Plus I engaged the question by thinking about books as teaching vehicles, not necessarily through a lens of personal enjoyment or self-development. What book, written for students, I tried to ask, is the best that a school could choose to teach. The written for students part eliminated some of my all time favorite books–To Kill a Mockingbird and Animal Farm for example–and i am not arguing that they should not be taught inschools. They should. Please teach them. And teach Lord of the FLies while you’re at it! But in the category as defined I nominate Lois Lowry’s The Giver. Here’s why:

1. The dystopian novel is a powerful genre from a teaching perspective. To me it is a response to totalitarianism. It’s important for citizens to understand why totalitarianism is so destructive and that it is destructive even when the rulers are not overtly and intentionally tyrannical, that “evil comes about through our best intentions.” This is a very mature idea.

2. Plus the totalitarianism connection means lots of outstanding historical and literary connections—to Animal Farm for example, or to North Korea. So there’s lots of additional fiction and non-fiction students can read and write about. And yes, there is some patriotism showing through in my loving so much a book that I read to be about resistance to totalitarian thinking… even totalitarian thinking that starts off benign.

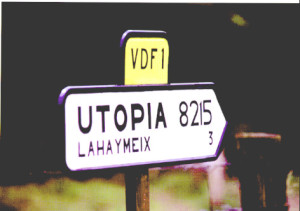

3. The book features a gradual revelation of the true nature of society… the community appears to be plausibly utopian or at least a decent place at first, but the book reveals its destructiveness and inhumanity incrementally. You learn this by assembling pieces, for the most part, until the powerful “release” scene where it all becomes clear. The book teaches skepticism of group think and valorizes independence and autonomy of thought. It’s very easy to take freedom for granted when you’ve always had it and when tyranny is always labeled for you in advance.

4. The ending remains unresolved and resists allowing readers to put challenging ideas to bed. An ending where good is not rewarded and evil not punished or where—at least—a sense of optimistic transcendence does not pervade–is unusual in youth literature. The Giver offers this but goes one step further by leaving even what happens at the end unresolved. It’s not actually clear (well, wasn’t until the sequel came out) whether Jonas survived at the end or whether he was dying. This was a very powerful moment for both of my two children, though they read it very differently. One was intellectually fascinated with the uncertainty and liked to practice reading the ending in two different ways; the other insisted that Jonas had survived and got deeply upset when I suggested that there was evidence to suggest that this might not be so. That child needed Jonas to live in a way I still don’t fully understand. (It’s probably a reflection of parenting.)

5. The role of language in a society’s ability to perpetuate deception is a constant theme. The book exposes young readers to the idea that the words we give things guide our perception of them and that people exploit this aspect of language. You learn here about the capacity of a society to develop sanctifying narratives. The book provides the opportunity to see your own world—and the rift between it and the language that describes it–through new eyes.

6. It stresses values that are good for school age kids but also timeless and not totally conventional—the importance of love and sacrifice for a child/sibling; selflessness and endurance in the face of pain. Even the complexity of its view on the role of pain in society… more or less that it is a necessary evil and the flip side of joy is a good antidote for an often self-indulgent society (ours, that is, rather than the community.)

7. The book is artfully written, with reserve and discipline, the descriptions of shocking events delivered with muted control. I remember reading Virginia Woolf in college. At some point the death of an important character is related in parentheses, like an after- thought. (“So and so, having died years before…”). There’s an element of that here. The text doesn’t always “sell” its critical moments. No trumpets sound. The watershed moments sometimes come burbling past like gold dust floating in a stream. Love that.

It’s not a perfect book, I recognize that. (Would that be a good thing? That seems like the idea for a novel in and of itself). I sometimes think I could do without the stirrings chapter for example, but then I make my peace with it and remind myself about the complexity of its vision.