02.12.20Emily DiMatteo Builds Knowledge Through Embedded Nonficiton

I’m excited to share this video of Emily DiMatteo’s English class.

First, it’s a great example of how Embedded Nonfiction can infuse a discussion with background knowledge and thus build its rigor. That’s an idea we’ve been passionate about for a while but have recently come to realize it hard to implement well without a curriculum.

And as it happens Emily is teaching a lesson from our new curriculum in this video so that’s a second reason to share the video and offer some thoughts.

And then there’s Emily’s exemplary teaching which you’ll notice right away.

Setting: Emily teaches 8th grade English at Cincinnati Country Day School.

She and her students are reading the section from George Orwell’s Animal Farm where Squealer attempts to manipulate the animals’ memories of Snowball’s role in the Battle of the Cowshed.

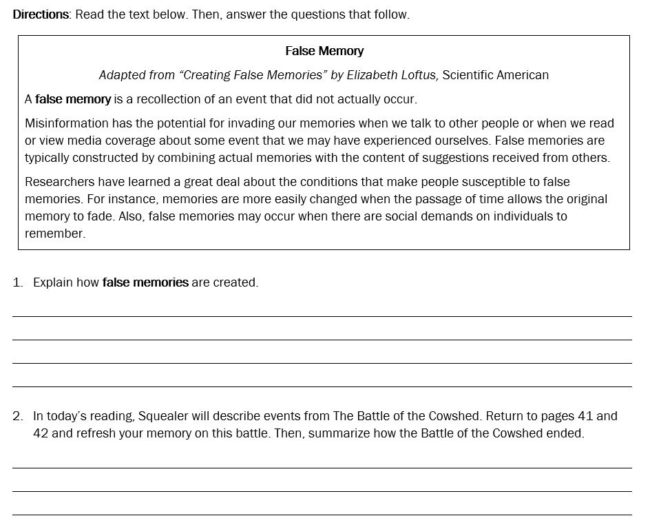

She sets up the discussion in the Do Now by asking students to read a short nonfiction article on false memories. Here’s what that looks like:

And here’s what it looks like in action with her students:

First you can see Emily asks her students to distill the article into three key takeaways about the ways memory can be manipulated. Yes, they they will use this information to understand what Squealer does in the book but they also now have useful background information about memory construction that they can apply for the rest of their lives. Emily has both built their background knowledge and also used it to help them get more out of the book.

Incidentally they’re also practicing reading scientific text, which is challenging is different ways from fiction. For example with key information conveyed in the most undemonstrative of passive voice sentences: “For instance, memories are more easily changed when the passage of time allows the original memory to fade. Also, false memories may occur when there are social demands on individuals to remember.”

We especially loved her transitions:

“So, yes, this is a book about talking animals and yet false memories are things that we as humans experience.”

and

“We don’t want to be subject to these manipulations. We know what happened in the battle of the cowshed. What was Snowball’s role?”

She sends that question to Alex via a genuine and inclusive Cold Call and Alex does a super job of summarizing most of what’s important to know. But, crucially, his excellent answer leaves our Snowball’s bravery and courage in battle- how he lead fromt he front and was wounded. Many teachers would merely praise an answer like Alex’s but Emily goes back to him with a follow-up (Stretch It or a Right is Right as you prefer): “Did he just direct people? Just supervising?”

It’s important to note that Emily prepared for this lesson by scripting her desired answer for key questions. This is how the noticed immediately the key gap in an otherwise strong answer. It’s hard to see those kinds of gaps, I argued in a recent post, unless you know what you’re looking for.

Now she’s set up to re-read the text and apply the lens of the article- to study the technical details of Squealer’s manipulation in Orwell’s story. And of course the discussion will be all the richer.

The use of nonfiction to build knowledge and enhance the rigor of discussions is a great move but as my colleague Emily Badillo notes in an upcoming article about why we decided to write a curriculum, over time training teachers we’ve found that often an idea like embedded nonfiction was powerful but also posed logistical challenges.

“Teachers weren’t able to go home and source short nonfiction passages about resistance movements in wartime, for example.” In fact this was why we Who knew where to find such an article, and once you found it, it needed editing — there were long digressions about less relevant topics or part of the key information was in one article and part of it was in another. It took time teachers didn’t have, especially preparing lessons after making dinner and just possibly putting their own children to bed.”

Lessons of real substance require work-sharing and support. Teachers rarely take courses in instructional design, Robert Pondiscio pointed out in a recent commentary. It’s a completely different skill from teaching a lesson, but one we assume teachers will naturally be able to do well. “It’s like expecting the waiter at your favorite restaurant to serve your meal attentively while simultaneously cooking for twenty-five other people—and doing all the shopping and prepping the night before. You’d be exhausted too.”

So one of the results of this lesson, we hope, is students with deepened knowledge about the world experiencing a great book brought to life. But another we hope is a great teacher like Emily going home at the end of the day of teaching outstanding lessons to tuck her own little ones in and get enough rest to get up the next day and deliver yet another outstanding lesson.

Want more on our curriculum? Check it out here.